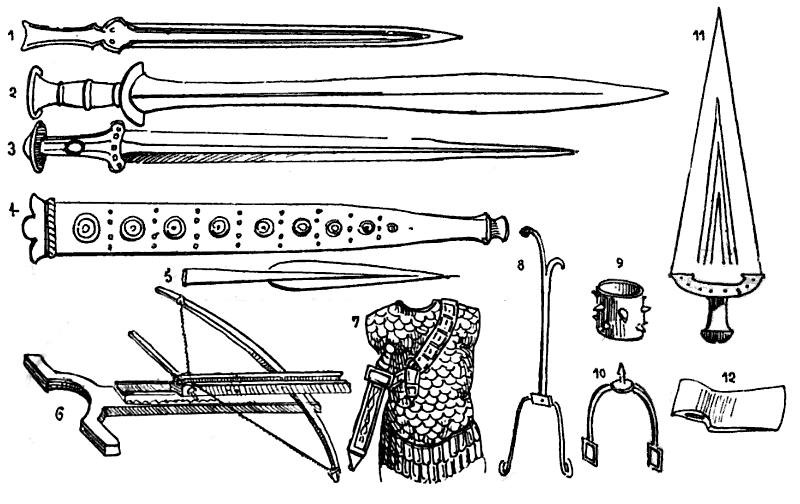

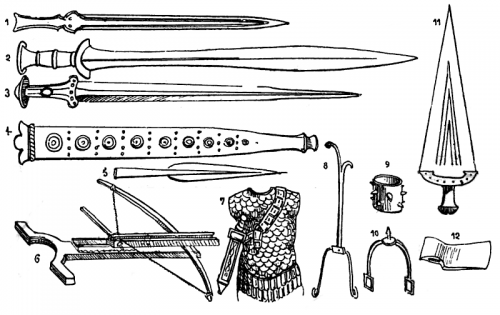

In Monday’s post, I took a closer look at some of the set dressing in one of our previous shows. The props included details which were relevant to the play but which would have never been visible to the audience. Why would anyone do that?

There’s a saying (I first heard it from Bland Wade at UNCSA) that if the prop is crap, the actors will treat it like crap. There is a lot that goes into a play: lights, sets, sound, theatre architecture, publicity, etc. For individual actors, they mostly share all of this with the rest of the company. The only pieces they have to themselves are their costumes and their props. If an actor is given a prop which is poorly made, misshapen, or otherwise less-than-stellar, it may feel like a bit of an insult; everybody else gets treated well, but he is left holding something that looks like an old candle stuck in a potato and wrapped in gaff tape. If it feels like a throwaway prop, he will act as though it can be thrown away.

When an actor is treating his props like crap, it may creep into his acting as well. He may still give his more important lines their proper reading, but the less important ones—the “throwaway lines”, if you will—will start to be treated with less care and thought. After all, if the theatre does not care enough to give him a well-constructed prop, why should he care enough to be emotionally focused for every single line?

That’s not to say that actors cannot overcome difficult working conditions, or that they only work well when they are coddled and pampered. What I am describing may not be conscious or done purposefully. But just like a dog can pick up an owner’s emotional state of mind even in the absence of any visible or verbal cues, so too can an audience pick up the invisible dissatisfaction of an actor even when he is trying his best to hide it. It is no coincidence that when you hear about the great flops of theatre and film production, you also hear about how bad it was working on them; in-fighting, personality conflicts, incompetence and other bad working conditions often go hand-in-hand with box office failure.

Contrast that with a production where everybody feels like they are taken care of. An actor receives a prop which looks like it was carefully built. Any notes or suggestions he gives to make it easier to work with are taken care of in a timely manner. He begins to feel that the theatre cares about every little detail and is working hard to do the best work they can. He steps up his own game, and works as hard as he can, because nobody wants to be the laziest person on a team. Small actions can ripple through a group of people and move them all in a positive or negative direction.

So take care in everything you do. You do not necessarily need to write a character’s phone number on a card which only the actor can see, but be aware that all your props add meaning to the show for the actors who use them.