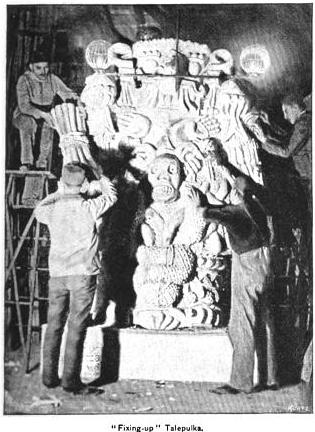

The following is an excerpt from “Behind the Scenes of an Opera-House”, written in 1888. The author, Gustav Kobbé, tours the backstage of the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. Be sure to check out the previous excerpts on constructing a giant “Talepulka” idol and introducting the series when you are finished here!

Behind the Scenes of an Opera-House, by Gustav Kobbé.

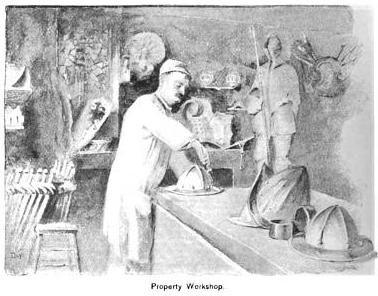

The first feature of an operatic production to have the benefit of a rehearsal is the scenery. As soon as the scenic artist and the scene-painters have finished their work the stage-manager orders a scenic rehearsal. This might be called a performance of an opera without music. The scenes are set up and changed, light effects tried, and mechanical properties like Talepulka, the “Lohengrin” swan, and the “Siegfried” dragon “worked” and tested until all goes as smoothly as it should at a performance. This is a rehearsal for the men who set and change the scenes—the master-machinist and his subordinates—and for those who manage the light effects—the gas-engineer and the “gas-boys”—and for the property-master and his men. Before the scene can be set it is necessary to “run the stage,” that is, to get everything in the line of properties, such as stands of arms, chairs, and tables, and scenery, ready to be put in place. If there is a “runway,” which is an elevation like the rocky ascent in the second act of “Die Walküre,” or the rise of ground toward the Wartburg in “Tannhäuser,” it is “built” by the stage-carpenters; and for this purpose the stage is divided into “bridges”—sections of the stage-floor that can be raised on slots. Meanwhile the “grips,” as the scene-shifters are called, have hold of the side scenes ready to shove them on, and the “fly-men” who work the drops and borders are at the ropes in the first fly-gallery.

The scene set, it is carefully inspected by the scenic artist and stage-manager, who determine whether any features require alteration. A tower may hide a good perspective bit in the drop: it may be found that a set-tree at the prompt-centre second entrance will fill up a perplexing gap—but changes are rarely needed after the scene has been painted, because a very good idea of it was formed from the model. The length of a scenic rehearsal depends upon the number of the light-effects and mechanical properties. For instance, in the first act of “Siegfried” the light-effects are so numerous and complicated that it is a current saving in opera-houses that the success of this act is “all a matter of gas.” When all effects and contrivances of this kind have heen thoroughly tested, the stage-manager gives the order: “Strike!” The “grips” shove off the side-scenes, the flymen raise the drops, the “clearers” run off the properties and set-pieces, and the stage-carpenters lower the bridges. The scene of the second act is immediately set, and the time required for the change of scene noted. If the change is not so quickly accomplished as it should be, it is repeated until the weak spot in the work is discovered.

…

When all know their parts, the stage is at last given up to features of the productions other than the scenery. The work is performed with scenery, light-effects, properties, chorus, ballet, and supers, but without the principals and orchestra, the solo répétiteur being at the piano. There are two or three such “arrangement” rehearsals for drilling the chorus and supers in the stage “business.” These rehearsals are followed by two in which the artists take part; the final test being the general rehearsal with orchestra. Then at last the work is ready for production.

First printed in “Behind the Scenes of an Opera-House”, by Gustav Kobbé. Scribner’s Magazine, Vol. IV, No. 4, October 1888.