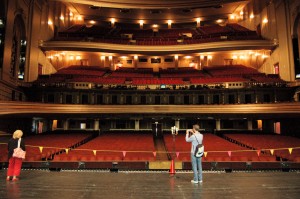

The following is an excerpt from “Behind the Scenes of an Opera-House”, written in 1888. The author, Gustav Kobbé, tours the backstage of the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. Be sure to check out the previous excerpt when you are finished here! The following details the construction of a large idol for the Met’s 1888 production of “Ferdinand Cortez”. As an added bonus, you can read the original New York Times’ review of that production.

Behind the Scenes of an Opera-House, by Gustav Kobbé.

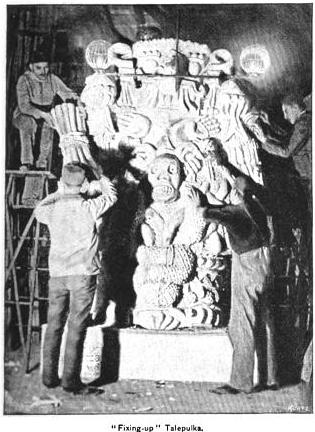

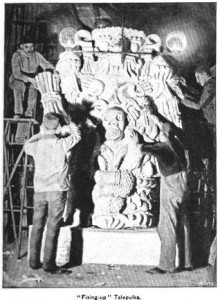

[T]he property-master had made out a list of the articles to be manufactured in his department. He had not been hampered by the problem of historical accuracy. He found drawings of Mexican antiquities from which he made sketches of the Mexican implements of war and peace to be used in the opera, and from a genuine Mexican relic of that period, seen by chance in the show window of a store, he obtained his scheme for the principal property in the work, the image of the god Talepulka. He found he could have all these historically correct, except that he did not think it necessary to go to the length of decorating the idol with a paste made from a mixture of grain with human blood. A problem arose, however, when he considered the construction of the idol. He ascertained from the libretto that the idol and the back wall of the temple are shattered by an explosion, and that, just before the catastrophe, flames flash from the idol’s eyes and mouth. He consulted with the gas-engineer, who had already considered the matter, and concluded that it would be most practical to produce the flames by means of gas supplied through a hose running from the wings.

The property-master then made the following note in his plot book: “Flames leap up high from the heathen image—the gas-hose must be detached and drawn into the wings immediately afterward so as not to be visible when the image has fallen apart.” The necessity of having the gas-hose detached determined the method of shattering the idol. It is a theatrical principle that a mechanical property should be so constructed that it can be worked by the smallest possible number of men. This principle was kept in view when the method of shattering Talepulka was determined upon. The god was divided from top to bottom into two irregular pieces. These were held together by a line, invisible from the audience, which was tied around the image near the pedestal. Another line, leading into the wings, was attached to the side of the top of one of the pieces. At the first report of the explosion a man concealed behind the pedestal, whose duty it also is to detach the gas-hose, cuts the line fastened around the idol, and the pieces slightly separate, so that the image seems to have cracked in two jagged pieces. At the next report a man in the wings pulls at the other line and the two pieces fall apart.

The manner in which the effect of flames flashing from the eyes and the mouth of Talepulka was produced was only outlined in the statement that it was accomplished by gas supplied through a hose. The complete device of the gas-engineer, a functionary who in a modern theatrical establishment of the first rank must also be an electrician, was as follows: Behind the image the flow of gas was divided into two channels by a T. One stream fed concealed gas-jets near the eyes and mouth, which were lighted before the curtain rose and played over large sprinkler burners in the eyes and mouth. These burners were attached to a pipe fed by the second stream. When the time arrived for the fire to flash, the man behind the pedestal turned on the second stream of gas, which, as soon as it issued from the sprinkler-burners, was ignited by the jets. By freeing and checking this stream of gas the man caused the image to flash fire at brief intervals. Thus only two men were required to work this important property.

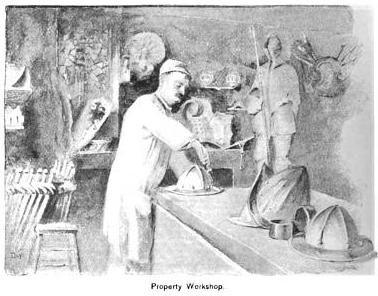

The idol was but one of four hundred and fifty-six properties which were manufactured on the premises for the production of “Ferdinand Cortez,” and when it is considered that the average number of properties required for an opera or music-drama is three hundred and fifty, it will be understood that the yearly manufacture of these for an opera-house which every season adds some three works to its repertoire is an industry of great magnitude. For instance, one ton and a half of clay was needed for modelling the Mexican idol, and that property represents three months’ work. It was first sketched in miniature, then ”scaled”—that is, projected full size on a huge drawing-board—next modelled in clay, and then cast in plaster. The modelling and casting of properties are done in a room in the basement of the building, on the o-p-side [Eric: opposite-prompt side, in this case, stage-left] of the stage. The idol was cast in twenty pieces. These were transferred from the modelling-room to the property workshop on the third floor of the building, prompt side, where are also several other rooms in which properties are made, the two armories, the scenic artist’s studio, and the property-master’s office. In the workshop the properties are finished in papier-maché, the casts being used as moulds. They are not filled with pulp, which is one method of making papier-maché, but with layers of paper. The first layer is of white paper, moistened so that it will adapt itself to the shape of the cast. Layer after layer of brown paper is then pasted over it. The cast having been thus filled is placed in an oven heated by alcohol, and baked until the layers of paper form one coherent mass the shape of the cast. Properties thus manufactured have the desirable qualities of strength and lightness.

First printed in “Behind the Scenes of an Opera-House”, by Gustav Kobbé. Scribner’s Magazine, Vol. IV, No. 4, October 1888.