The following is the fifth excerpt of an article which first appeared in 1905 in the St. Louis Republic. Check out the first, second, third, and fourth parts for the full story.

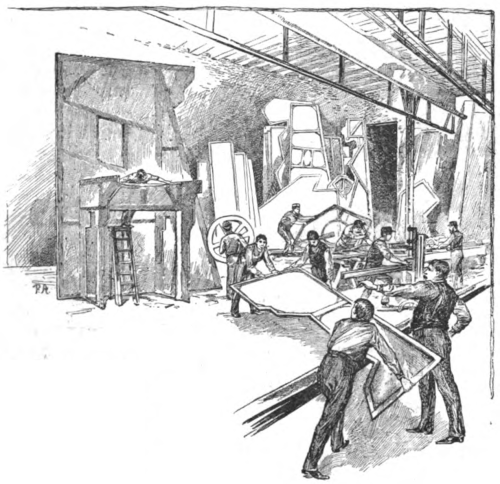

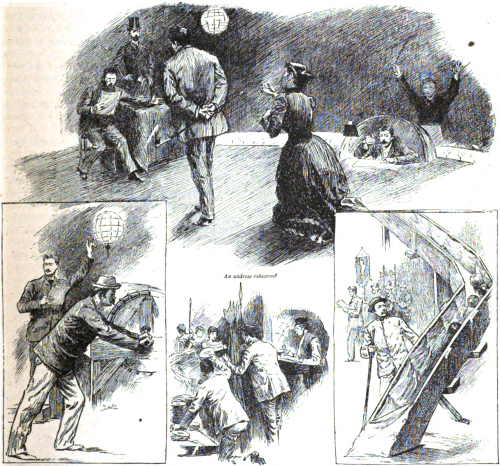

This is the proposition which faces every property man of the modern theatrical company of any proportions whatever. He gets the lines, the scenery, plot and the details of the situation as quickly as do the stars. Every rehearsal he attends with the same regularity as do the participants. Under the eye of the stage manager he sees and hears repeatedly the play as it reaches its perfection, and by the time that the first performance is reached he has as perfect a knowledge of each little speech as even the minor characters, and knows the entrances and exits for each as well as does the stage manager, who is the director general.

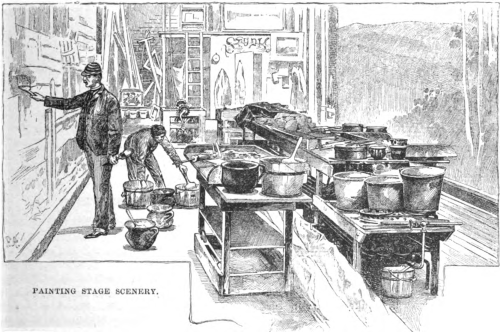

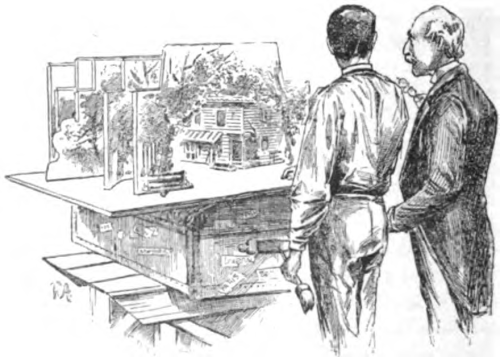

After he has secured a general idea of the construction of the play he gets the directions from the playwright as to what the costuming will be and what will be needed by the players in giving absolute realism to the performance. After the greater portion of these “props,” as the profession technically calls the articles collectively, have once been purchased, there is little need for further worry, as they will last through the ordinary season without replenishment. But the incidentals must be secured every night or two, and it is the constant alertness which is thus necessary which makes the life of the property man a burden at times.

After the first two or three weeks the property man has a comparatively easy time of it. The rollers have been well greased and things are moving smoothly. If business has opened up well it means that for a run of many weeks and possibly months the company will remain at the metropolitan theater, which saw its “first night.”

Then the trip to the South or to the West begins, and coincidentally opens the siege of trouble for the property man. Out of a month’s time at least half of the performances are given at “one-night stands,” with long jumps between the towns, and it is at this stage of the game that he earns his salary.

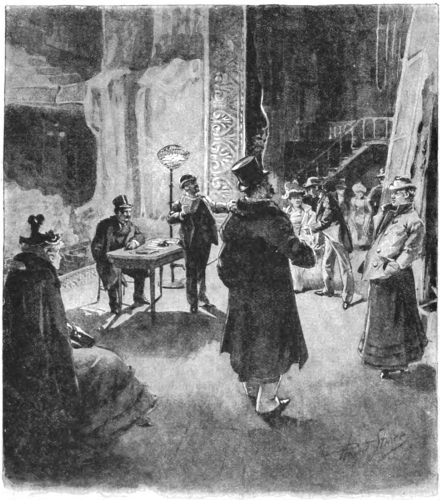

The advance man has furnished the local theater staff with a list of the “props” which his company will demand on the night of the performance, and several weeks ahead the property man of the house knows what will be necessary for him to secure, and under usual circumstances the stuff comes out of the supply of furniture, bric-a-brac and staple articles of stage furniture which the up-to-date theater carries in stock now.

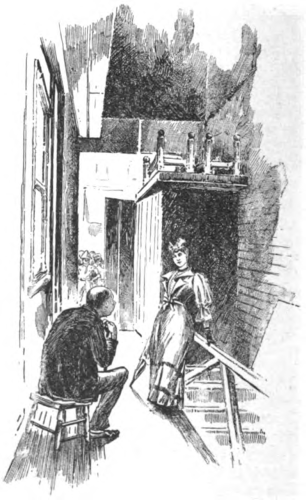

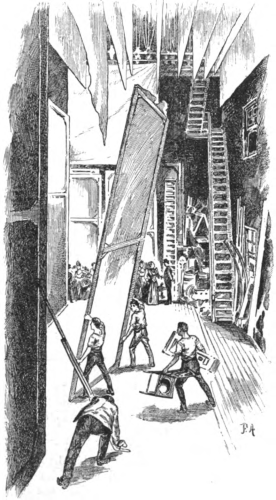

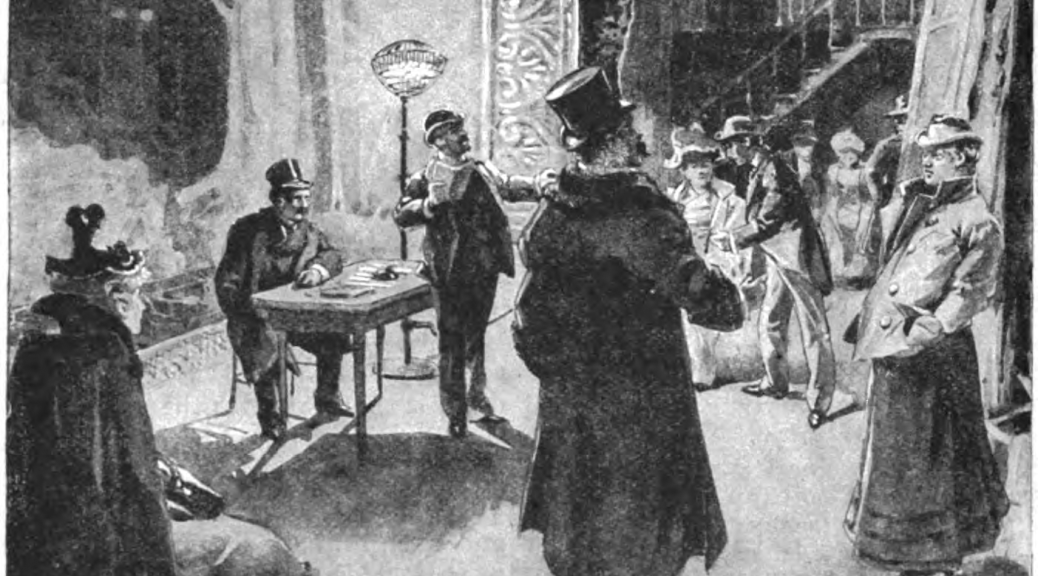

After an all-night and all-day ride, possibly, the property man of the company reaches town with the balance of the company. While they are off to a hotel for rest and refreshment it is his first duty to superintend the unloading of his portion of the baggage and then reach the theater at the earliest possible moment. Under no circumstance is there an excuse permitted for his failure to have everything ready for the curtain to rise at the appointed moment, and so he gets to the house on a run and checks over the list of house “props.” He takes to himself a dressing-room hard by the principal stage entrance and opens up his own stock of dry goods, clothing, groceries, hardware, boots and shows and notions, to say nothing of the supply of liquors.

If he is fortunate in arriving early in the city and finds that all has been done as required by the contracts, and has no need of skirmishing the town over to replenish some of his own supplies, he gets then a chance to eat if he can get through in time to return to the theater by 7 o’clock.

Originally published in The St. Louis Republic, January 1, 1905.