The following comes from an 1892 Theatre Magazine article:

Probably the most ingenious stage machinery that the Meininger Company possesses are their contrivances for producing thunder in all its varied forms. Four distinctly different apparatuses, every one perfect in its way, are used for this purpose. The result accomplished with them is as close an imitation of nature’s thunder as human ingenuity will ever be able to make.

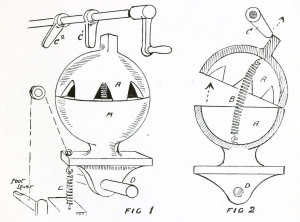

The principal apparatus consists of several wooden boxes, about one foot square, which run along the entire length of the wall from roof to cellar. Inside of each box, from one to two feet apart, slanting boards are placed, running about half way across the interior, as shown in the cut. At the very top of the box are several compartments, in which a number of iron balls of different sizes are placed. By means of a rope-and-spring attachment any one of these compartments can be opened from the stage, and thus the balls contained in it permitted to tumble down their tortuous course to the cellar. The noise that this creates is almost exactly like the thunder of a near storm. At first, owing to the great height from which the balls are started, the sound reaches the audience but faintly, growing gradually louder and more reverberating as the descent of the balls becomes more rapid and as they reach the level of the stage. With their passage down into the cellar the noise again grows gradually less and more distant. With this apparatus alone, however, no low, gradual dying out effects or that faint, gradually increasing rumbling of a far-away approaching storm can be given. For this purpose, then, an instrument made on the principle of a drum is called into service. It is a huge, square wooden box over the top of which a thick vellum is tightly stretched.

The operator uses, besides a couple of drumsticks, about a dozen wooden balls of various sizes, which are rolled around on the parchment in a most dexterous manner. The sounds produced in this way can be perfectly graduated according to the number and the size of the balls used and the manner in which they are rolled.

To simulate the crashing of a thunderclap a contrivance built on the principle of a policeman’s rattle is employed. On top of a huge box, about ten feet long and four feet square, a number of wooden slats are fastened so that they act like springs. A cylinder with wooden pins, resembling somewhat the cylinder of a music-box, is at one end of the box. On being turned the pins lift and drop the end of the slats in rapid succession.

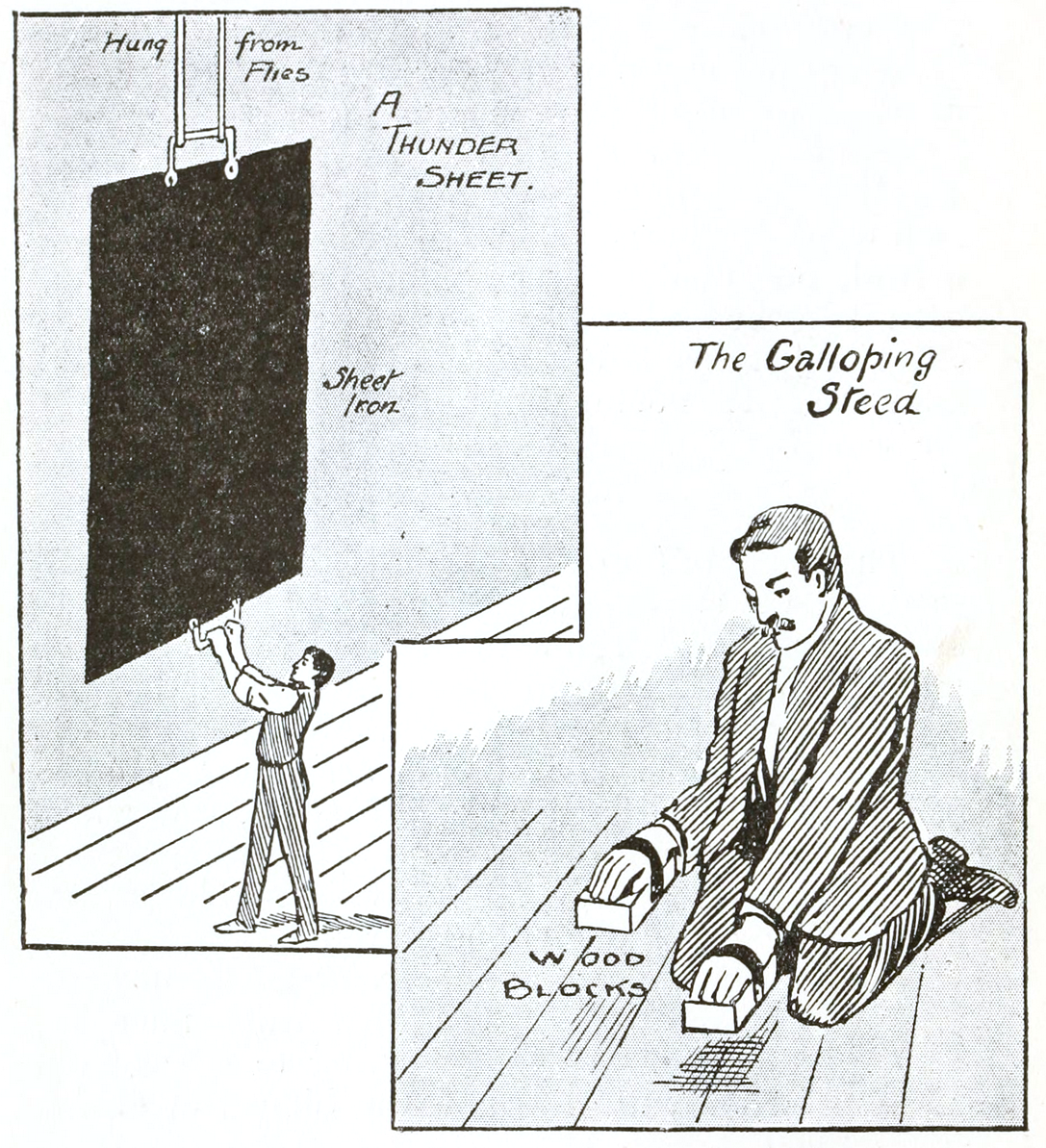

The fourth device to contribute to the various “thunder effects†is the familiar sheet of iron, which is too old and well-known an institution to require description. All the apparatuses mentioned are in different parts of the theatre back of the stage and in the loft, so as to avoid having the sound come from one direction, and by their skillful manipulation and the exact blending or combining of the different sounds at the proper moment remarkably realistic effects are produced.

The lightning by the Meiningers is done with a camera lucida, an invention by one Baehr, of Dresden. It is a contrivance resembling a big magic lantern and is worked on the same principle. A powerful electric light is burned inside of it. Behind the focus is a revolving disk of dark glass plates, on every other one of which are faintly traced the outlines of different kinds of lightning. The disk is revolved very quickly, so as to throw the flash on the canvas for only an instant’s duration. The sheet lightning is also produced with an electric apparatus, one of which is used on either side of the stage.

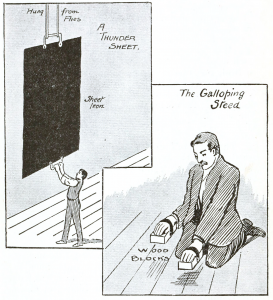

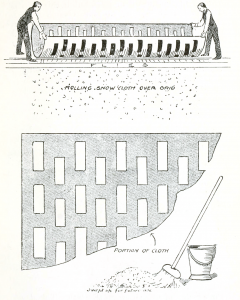

The pouring and pattering of rain and the beating of hail require four different contrivances. The most novel of these is a wooden box, about twelve feet long and six inches square, inside of which are numerous slanting sheets of tin, punctured with small holes. A number of peas are rushed continuously up and down the box, rolling over the puntured tin and tumbling from one sheet to the other in a manner like that described of the iron balls in the “thunder box.†There are two or three of these “rain-boxes†in the possession of the Meiningers, each one differing from the other only in the angle and width of separation of the tin sheets within.

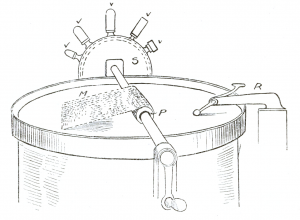

A soft spattering of rain is produced with an ordinary sieve on which a handful of peas are rolled around, while a more violent downpour, mingled with pelting hail and lashed by the wind, is given by means of a large revolving cylinder of wire gauze, inside of which are a lot of round pebbles.

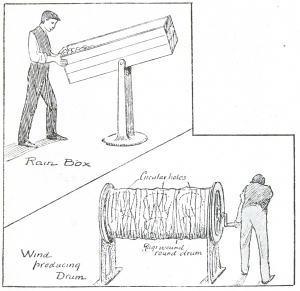

For the marvelously realistic gusts of wind in the storm scene of “Julius Cæsar” an apparatus is employed which closely resembles a large revolving fan used for ventilating purposes. In this case, however the tips of the fan as it revolves scrape lightly against a broad strip of stiff silk, thus giving a swishing sound.

“Ingenious Stage Machinery.” Theatre Jan. 1892: 31-32. Google Books. Web. 28 Feb. 2017. <https://books.google.com/books?id=QR1LAQAAMAAJ>.