The following article first appeared in the 1886 edition of The Cornhill Magazine.

Formerly the scenic artist was strictly a scene painter, and his work was simply to cover canvas with beautiful and effective pictures. To this class belonged Grieve and Telbin, and Stanfeld, who later became a Royal Academician. The large bold style required for scenery is a fine training, and at this moment it is easy to distinguish one of Telbin’s landscapes, so poetical and rich is the treatment. The artist of the Lyceum, Mr. Craven, is also remarkable for richness of colour, freedom of touch, and much grace and fancy.

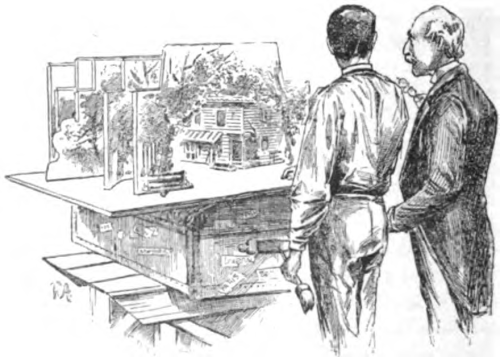

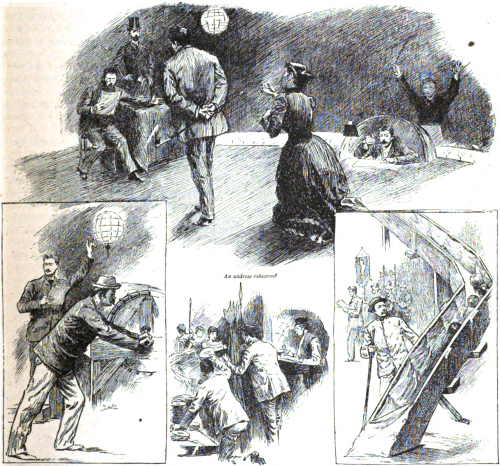

It is curious to visit the painting-room of this theatre, which is high up in the roof, when some great and costly piece is being got ready. Here on a table we find a small model stage, like a toy theatre, but which is carefully made to scale, with all the entrances, &c., marked. The artist first paints his little scenes on cardboard, cuts out the doors, windows, &c. exactly as he intends it to be on the real boards below. He has, besides, large plans of the stage, done to measure, on which can be arranged all the portable structures in their exact position. Now arrives the clever manager, who is possessed of much suggestive taste. The little scene is set for him—it suits—or he may suggest some more brilliant and effective idea.

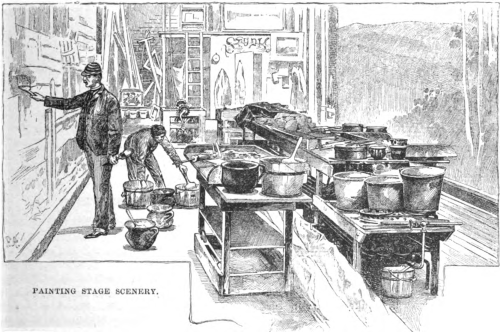

Meanwhile assistants are busy at the canvas hung on the walls, with rules six feet long, ruling the  perspective lines in black, or getting in the rough colours. Of course, only a portion of the scene can be painted at a time, as the room is a low one. In the great foreign theatres the canvas can be raised or lowered through a slit in the floor, or the wall made high enough, as at Drury Lane, to take in the whole scene.

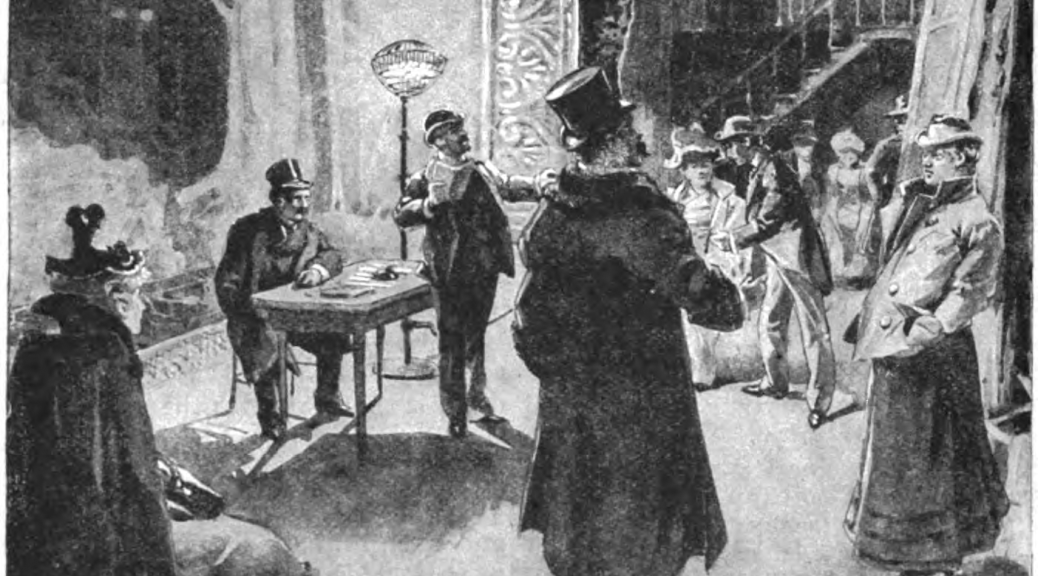

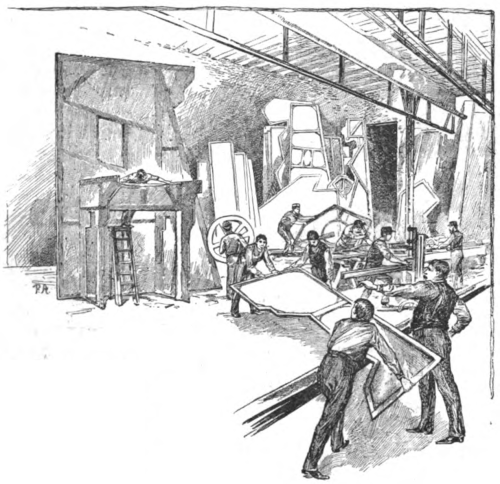

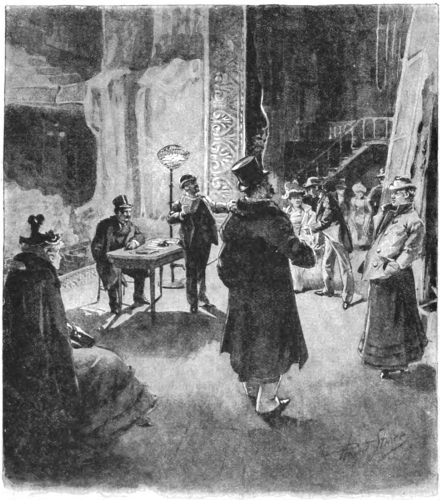

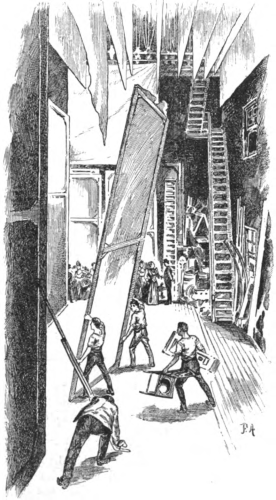

But in these times the scene builder has taken the place of the scene painter. Houses, bridges, porches, streets even, are all constructed in the carpenter’s shop. There is now no system for scenery; all that the stage manager requires is that his stage should be a perfectly clear, open, and unencumbered space on which he can launch his army of men to drag on and build up these great structures.

Formerly there were grooves for the scenes to slide in. At the sound of a whistle the scene was drawn away right and left, and we saw the grooves let down on hinges, and in which the new scene was to slide. All this is rococo and old-fashioned. In some of the older theatres one has often seen the two halves of a scene driven from right to left, the two men in their shirt-sleeves who moved them being quite visible, until the halves met in the middle with a sharp crack. Occasionally there used to be an imperfect joining, when, according to the old story, a fellow in the gallery called out, ‘We don’t expect no grammar here, but yer might make yer scenes meet.’

Smith, Elder, & Co., ed. “The Scenic World.†Cornhill Magazine 1886: 283-85. Google Books. Web. 23 Feb. 2016.