The following comes from a 1909 edition of the San Francisco Call. Besides the description of the props, pay attention to an early description of spike marks.

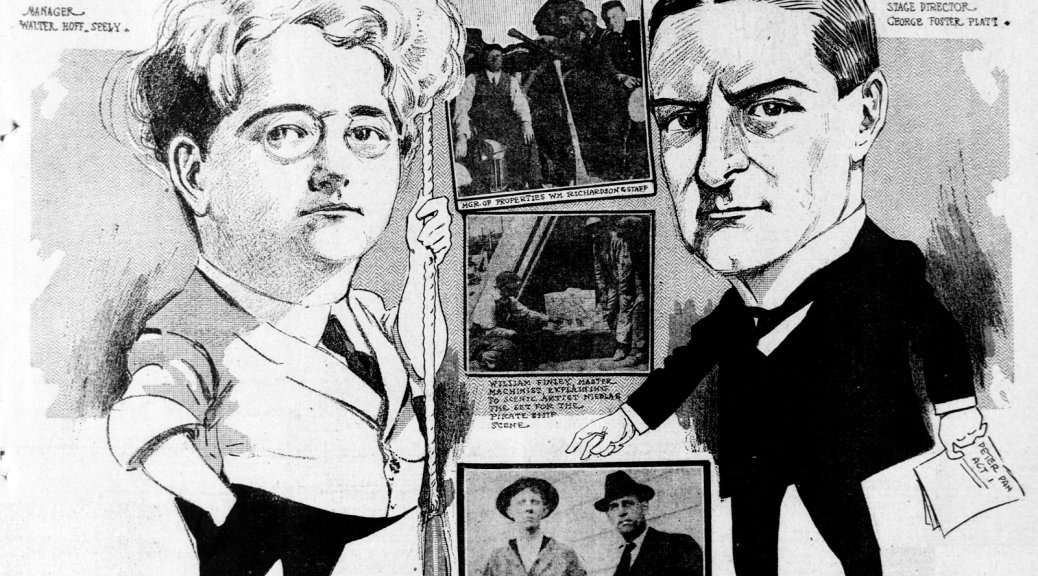

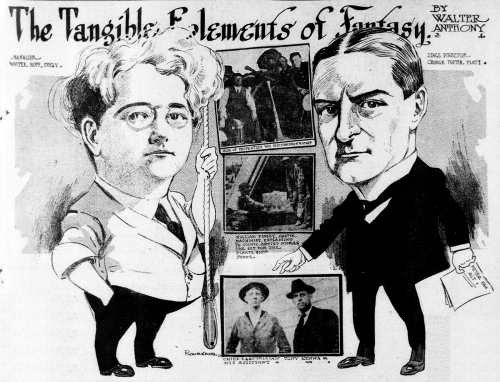

The Tangible Elements of Fantasy

by Walter Anthony

In the first place as you wander about the stage observing the traps which have been cut into the floor; the mysterious marks here and there which show the exact location of every individual piece of furniture and scenery; the accumulation of cannons and birds and dogs’ heads; the lion, the crocodile, which as tasted of Captain Hook’s hand and wants the rest of the pirate for dinner; the dog’s skin, that poor Harcourt has to perspire in; the maze of wires to swing the Darling children out of the window when Peter Pan teaches them the difficult art of flying—I say, when you take in the mass of mechanical detail which the production of “Peter Pan” requires, your admiration will grow for Barrie, the whimsical Scotchman, who conceived the whole thing; for Manager Walter Hoff Seely, who has not hesitated at putting $8,ooo into the production; and for George Foster Platt, the stage director, who is bringing all the ends of this fantasy together and is literally piecing together moonbeams and moth wings.

…

Then Stage Director Platt takes descriptions and roughly draws the scene, Ralph Nieblas, the scene painter, makes a model out of cardboard, with every measurement carefully indicated. When the model is done, it is an exact reproduction in miniature of what the scene is going to be like. Nieblas and William Finley, the head carpenter, get together and puzzle it out. Finley told me he had to be able to make anything from heaven in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” to hell in “The Black Crook.”

Plans and specifications, drawn by Platt’s imagination from Barrie’s imaginary pictures, are made and the work of producing the scenery and the properties begins. Meanwhile, the propertyman is scouring the city for accessories, such as the bell which is used on the ships; for in the pirate boat scene there must be a real bell with a real clapper, to emit real vibrations. William Richardson, who is the propertyman, is now in a state bordering on nervous prostration, for the strange things he has had to collect include everything that a fantasy could demand. “I got the bell at a ship chandler’s,” he said, “and a bad cigar for Captain Hook to smoke at every performance, but I will not tell you where I got that. It wouldn’t be fair to the pirate. I had to get a hook for him to wear after the crocodile has eaten his hand, and the list of things that I have raced around town for would bewilder the most enthusiastic shopper in the world.”

Anthony, Walter. “The Tangible Elements of Fantasy.” The Call [San Francisco] 11 Apr. 1909: 25. Library of Congress. Web. 8 Sept. 2015.