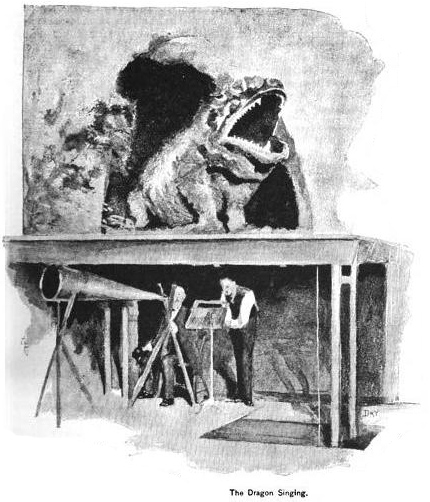

I previously shared an article from 1888 about a giant dragon named Fafner used in the Metropolitan Opera’s performance of Siegfried. It had a papier-mâché head, a canvas hide and curled leather scales. It could move its mouth, close its eyelids and issue forth steam from its lungs. So who created such an impressive piece of stage property?

It would appear a man named William “Old Bill” E. De Verna constructed it. He was born in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, NY, in 1834, and died in the same neighborhood in 1897. He had achieved enough prominence in the theatrical world to have an obituary published in The New York Times, with his occupation listed as “maker of theatrical properties.” According to the obituary

He built a large factory called in Bay Ridge the “dragon” factory, where he manufactured scenic accessories. When the Metropolitan Opera House was built he was engaged to supply all the properties used in the German opera. The big dragon of “Siegfried” was considered one of the most perfect examples of the property maker’s art.

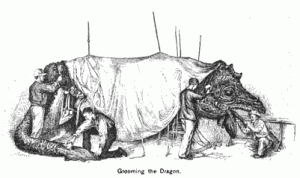

A second dragon was built for the Met around 1911. In 1937, the Metropolitan Opera made a few improvements to this second iteration of Fafner. A “New Yorker” article describes how they replaced his metal scales with a painted canvas hide to cut down on his weight.

Like the original, the 1937 dragon also had a papier-mâché brow. It could “prance around”, open and close its jaws and spread its fins. It was operated by two stagehands, Charley Walters and Paddy Downey, who had been playing Fafner since around 1922. They were not chosen for any specific reason; Phil Crispano, the head property man, “just told them to get in there one day.” The smoke from the dragon’s nostrils was at one time supplied by live steampipes, but has since been replaced with a vapor made from ammonia, muriatic acid and rose water (to improve the smell).

Interestingly, the 1888 article describes the scene with the dragon as lasting forty minutes, while the 1937 articles says it was over in just fifteen.

A new dragon was commissioned in 1948 to replace the “the ancient bundle of canvas and rubber hose the Met has seen fit to fob off for thirty-seven years as Fafner”. This one was built by Messmore and Damon, a company headquartered on West Twenty-Seventh Street in Manhattan. Messmore and Damon were known for the full-scale mechanical dinosaurs they debuted at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair.

According to another article in the “New Yorker”, this new dragon took advantage of the company’s prowess in mechanical engineering, as well as the new breakthroughs in materials available to prop makers. The jaw could move, the tongue could flick in all directions and the eyes could roll in their sockets. The whole cave was moved downstage so he could be seen better; traditionally, the dragon appeared far upstage, probably to conceal the limitations of dragon construction at the time. The paw of this Fafner actually dangled into the orchestra pit. He was also split into two pieces; his head came out of the wings downstage, while his tail appeared from the wings upstage to make it appear that a much larger dragon was present just offstage.

The 1948 Fafner’s teeth were constructed of solid maple, his tail was foam rubber and his claws had rubber tips. Real steam was used for his nostrils once again—the chemical smoke caused the singers to cough—though now it was provided by a portable steam generator.

And the cost for this modern marvel? A whopping two thousand dollars. Okay, so that’s actually just over $19,000 today, but still, being able to buy a custom working dragon for less than the price of a new car is pretty spectacular.