Dressing Interior Sets for the Motion Picture Camera

by E. E. Sheeley(originally published in American Cinematographer, 1923)

The dressing of moving picture sets calls for something more than a pleasing effect to the eye—any interior may be ever so pleasing in itself but its composition may be entirely conflicting when the camera angles are taken into consideration.

Every cinematographer knows how difficult it is to shoot an interior which, though probably beautiful to the eye, presents almost insurmountable obstacles to transfer its appearance to the screen just as beautifully. While an interior may, to all indications, be “tastefully” dressed, it may, on the other hand, involve such a series of clashing factors as to render impossible its being practically photographed.

Should Be Ready for Camera

When the cinematographer sets his camera up on an interior, that interior should be as nearly perfect as possible so that he will not be obliged to waste valuable time in making experiments in the shooting of the action of the characters before it becomes conclusively evident that the entire “dressing” of the set must be altered. If there is any experimenting—and there is plenty of it—to be done in the dressing of an interior, let that experimenting be done before the director calls his players and the cinematographer to the set for the making of the scenes in a production.

It is the duty, then, of he who dresses the interiors to exert every effort that the decoration of such sets be in accord with photographic possibilities rather than work against the camera and the cinematographer. Usually the fulfillment of such duties falls under the jurisdiction of the art director and cinematographers in his department who preside over the technical, the property and similar departments which carry out the actual physical dressing of the interiors.

Study Scenario for “Dressing”

The first step in the dressing is a careful perusal of the scenario so as to determine just what is needed. Here is where the severest difficulties very often arise. It may so happen that the scenario writer may recommend some certain interior construction and dressing, and it may be the case that the scenarist, though a very brilliant person in his line, may possess virtually no technical or architectural training so that the construction he recommends cannot be carried out at all if the interior is to be photographed; in fact, it would be necessary to give a set six walls in many instances in order to carry out the designation of the scenario department. It might be said here that if the scenarist, who does not have technical or architectural knowledge, would take it upon himself to learn as much as he could about the possibilities and the limitations of the camera, about the details which go to dress a set properly, about set construction even if he speaks only to the carpenter on the stage, he would increase his own efficiency immeasurably and prove an even more valuable man to his organization.

Every Step Considered

When the scenario is studied, those who dress the sets consider every step of action that is taken on the interior in question. The furnishings which go into that interior must aid the action as much as possible. Nothing that would obstruct the execution of the action may be used. Camera angles must be kept in mind at all times; nothing should be ordered that would violate the photographic factor in the least.

If the set does not house contemporary action but represents some fixed period, then every care must be made to furnish it correct to the slightest detail. We of course are familiar with the various furnishings and decorations which are in vogue today, so that an interior which calls for them naturally will not prove so hard to dress as an interior whose furnishings are of a period which has become strange to us.

Mathematical Calculations

Then there are all sorts of mathematical calculations to be made concerning the interior, and he who does not have a thorough knowledge of all branches of mathematics at his command will find himself at sea.

Property Houses Enlisted

When a list of objects which are deemed as suitable for the interior are finally drawn up, it is turned over to the “outside” man of the property department — that is, the man whose duty it is to assemble all the articles which are designated on the list. He makes a thorough canvass of all sources of such supplies — at the great property houses which have brought together for motion picture use materials from every part of the world. His duties are of the utmost importance, too, since the actual physical dressing of the set depends on him. He must know what an article’s camera possibilities are for certain uses. He must be able to pick objects correctly the first time so that time is not wasted in returning them to the property houses and exchanging them for others winch should have been selected in the first place. The “outside” or property man has also been given a copy of the script at the very beginning and he also studies it minutely with regard to period, given details, etc.

Effects With Props

Just as effects are to be made by the use of lighting, other effects are accomplished by the placing of objects in the dressing of sets. A picture placed here or an ornament there may eliminate bleakness or break a vacant effect. If great depth is to be shown in a minimum of set space, this may be accomplished by “forcing the perspective,” just as is done in drawing. Every interior must be balanced. Objects must be so planted that they fit in with every point of action that is to happen in the set.

Test of Sets

Before the set is turned over to the director, it is given the acid test within our organization when two cinematographers who comprise a special experiment department set up their cameras on the set in question and pass finally on its “photographic fertility.” If it is found that the set is cinematographically satisfactory, a chart which, with full data, has been especially prepared is turned over to the director who is to use it, pointing out the suggested angles which the experiments and construction have established as the best to shoot from. Of course when it is known which cinematographer is to shoot the set in question the props have been selected to harmonize with his own photographic individuality.

Originally published in American Cinematographer, vol. III, No. 12. March, 1923 (pp. 5-6).

About the Author: E. E. (Elmer) Sheeley was an art director for dozens of films between the 1920s and 1940s, most notably The Wizard of Oz in 1939.

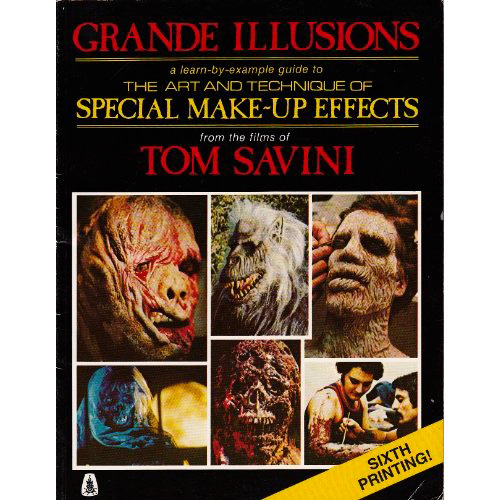

Happy Friday the Thirteenth! If you are a horror film fan, you must surely recognize the work of Tom Savini if not the name; he created the horror effects for the film, Friday the 13th. He has a book called Grande Illusions: A Learn-By-Example Guide to the Art and Technique of Special Make-Up Effects from the Films of Tom Savini

Happy Friday the Thirteenth! If you are a horror film fan, you must surely recognize the work of Tom Savini if not the name; he created the horror effects for the film, Friday the 13th. He has a book called Grande Illusions: A Learn-By-Example Guide to the Art and Technique of Special Make-Up Effects from the Films of Tom Savini. His resume of films is quite impressive for this kind of work; besides the aforementioned Friday the 13th, he has also done makeup and horror effects for Dawn of the Dead, Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter, Day of the Dead, Monkey Shines, Creepshow, and many more. In addition to influencing many horror effects artists working today, he also runs the Special Effects Make-Up and Digital Film Programs at the Douglas Education Center in Pennsylvania.

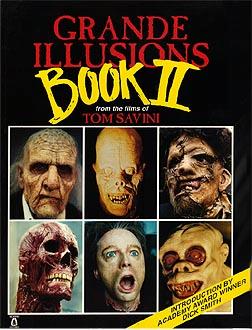

In the same vein, Grande Illusions: Book II

In the same vein, Grande Illusions: Book II presents another batch of films which Savini has worked on. This book also features tutorials on creating a breakdown of makeup appliances from a sculpted head, punching hair, and making a case mold from a bust. Though either book is good on its own, together they present a fairly complete picture of Tom Savini’s work and the techniques he uses to achieve it.