If your production is permitted to use live flame, a match can be one of the most frustrating props to get right. In real life, we barely notice when it takes a few attempts to light a match, but on stage, we want the match to light up on the first stroke. First we need to know about the two main types of matches: safety vs strike anywhere.

What is the difference between safety matches and strike-anywhere matches? A match requires a mix of chemicals in order to ignite, including phosphorus. On a strike-anywhere match, all the chemicals are contained in the head. On a safety match, the phosphorus is not on the match head, but rather on a special striking surface. It is only when you draw the match against that surface that you have the correct combination of ingredients. A strike-anywhere match can be lit against any surface with enough friction; a safety match needs a strike plate containing phosphorus.

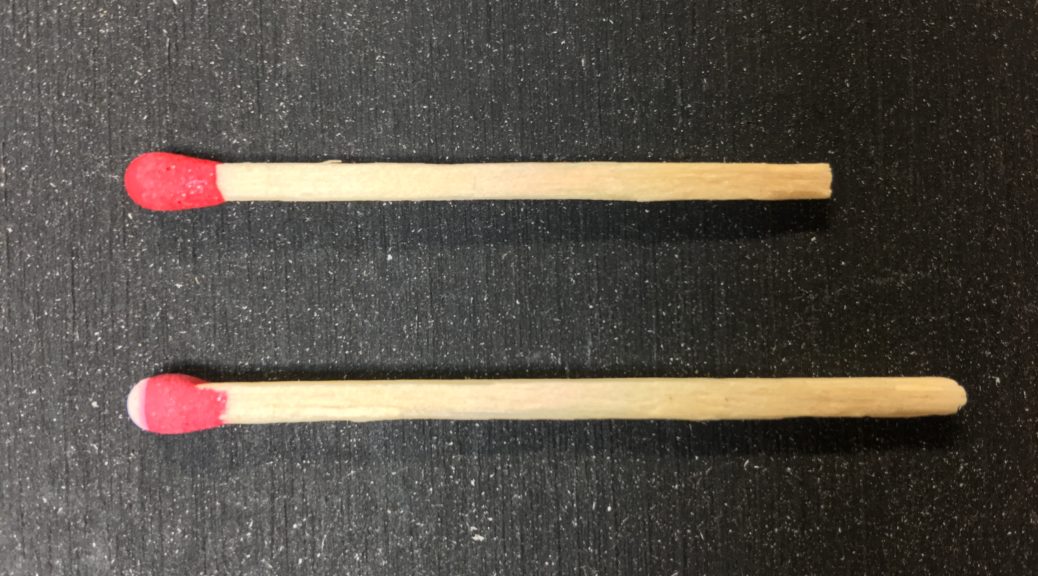

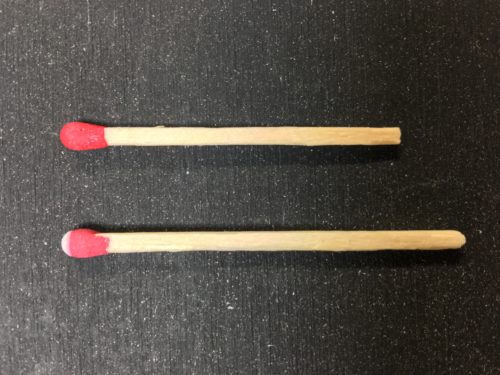

The above picture shows the visual difference between the two. The head on a safety match (top) is a solid color; usually red or blue, though newer ones can be green. The head of a strike anywhere match is red with a white tip; the white tip is the phosphorus.

In theatre, we want consistency, and most productions opt for the strike-anywhere match. You can light it off of a sheet of sandpaper; I found 300 grit is pretty good. A lot of shows will tape small rectangles of sandpaper on various hard surfaces around the set so the actor can light the match wherever they are. With a safety match, the chemicals on the striking plate are consumable, so the matches get progressively harder to light unless you switch out a fresh strike plate every so often.

Using strike anywhere matches takes some foresight, since it has gotten nearly impossible to just run out to a store and buy them. You probably need to order them online. They are not difficult to find, but they may take a few days to ship because of regulations against sending them by air.

You can buy in bulk, though they tend to lose their effectiveness over time. For optimum storing, keep them in an airtight container or bag along with a pack of silica gel desiccant.

As far as the historical accuracy of matches, both types appeared at basically the same time. The nineteenth century saw a lot of change and evolution in matches. You can find a lot of information online, but be careful with what you read; many sites will have interesting trivia about matches, but will neglect to tell you which matches were widely used and which were expensive novelties.

Basic archetypal wood matches using white phosphorus were widely used between 1830 and 1890. Many nineteenth century match boxes did not contain a striking surface, but rather had a loose piece of sandpaper inside that one used to light it. They also needed to be kept in an airtight container, so you would not see piles of loose matches out in the open.

The strike anywhere match as we know it came around the beginning of the twentieth century, as the use of white phosphorus was banned around the world and alternatives were found.

Safety matches began appearing around the middle of the nineteenth century.

Besides keeping your matches dry and making sure you have the correct striking surface, the other way to help your actors light a match is to use matches with a larger head and a sturdy shaft. Kitchen matches will often use thicker wood for their body than “standard” matches. Camping matches are typically beefier too; however, if they are “windproof”, it will be harder to blow them out, which can be dangerous onstage. Fireplace matches have some of the biggest heads; their shafts can often be nine inches or longer, but you can cut them down to whatever length you need.

One final disclaimer: the use of live flame onstage should only be done when you have the approval of the venue and the local fire marshal. Many jurisdictions will not allow any fire at all, even a single match. You need to take all possible precautions, including having someone backstage on “fire watch”, standing ready with a fire extinguisher. Wherever the actor disposes of the match, whether an ashtray or other container, you should fill with a bit of water, non-flammable gel (like Vaseline), or sand. The proper flameproofing of all props, scenery, and costumes around the match is also vital.