I came across the following article in The Bystander, No. 98, Vol 8, Wednesday, October 18, 1905. Sexist language aside, I thought it gave a glimpse of an interesting theatre company that many of us would not have thought existed at the time. It is also a fascinating article to present during Women’s History Month.

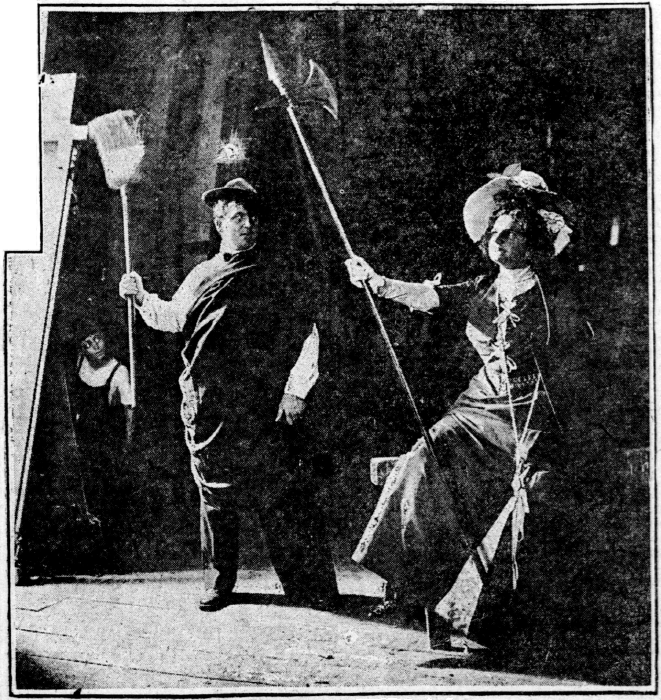

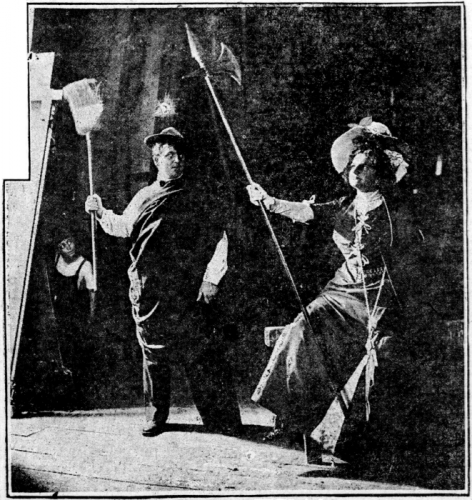

A Novel Theatrical Company:Â Financed, Managed and Run by American Women

(Mailed by our Correspondent in America)

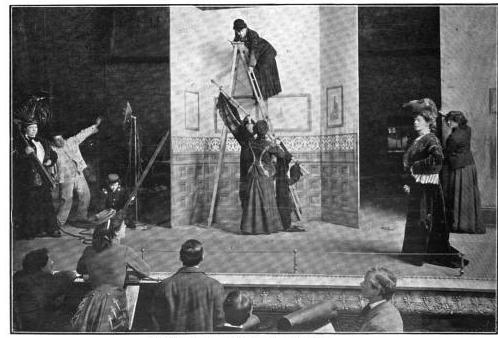

The American woman is proud in the knowledge that she can stand alone without the support of mere man. She has taken her place in the world of affairs, and now she is to prove that she can run, entirely on her own, that most difficult of businesses—a theatre. Miss Gertrude Haynes is at the head of a Company which will present a woman’s play, written by a woman dramatist, financed by a woman “angel” (this is as it should be). Advance agent, doorkeeper, treasurers, scene-shifters, attendants—all will be of the fair sex.

Miss Haynes is one of the best-known new stars in the country, her “Choir Celestial” having been presented in all of the theatres of the big circuits. She was the originator of the religious act on the stage, and has won both fame and fortune. But let her speak of her own project:—

“My determination to use women stage hands, advance women, and ticket-takers, is not a freak notion,” said Miss Haybes. “I have tried women for the work and found them better than men. They are faithful, work harder, and can always be trusted to be on hand. And that is more than can be said for some of the men who have been in my employ.

“My sister, Miss Tessie Haynes, went out as my advance agent two years ago, and her success was remarkable. No man ever did so well for me. And it wasn’t six months before she was engaged.

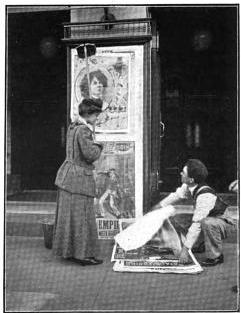

Some of Miss Tessie Haynes’ experiences were more strenuous than most men in the same position are called upon to undergo. In Chicago, she encountered a strike of bill-posters, and could not get the Company paper out. Finding that appeals to the strikers availed nothing, the plucky little woman determined to put up her own bills. Hiring a wagon, she went out supplied with paste bucket and brush, and posted the bills.

Her action caught the fancy of the men, who cheered her bravery, and her bills were not disturbed. She has the record of being the only woman bill-poster in the world.

Miss Gertrude Haynes is not exactly preparing for trouble, but she is prepared to meet it if it comes. The man who thinks to have a joke at her expense will “get left” as his countrymen say.

Thus: “My property woman weighs 160 pounds, is strong and vigorous, and can hustle a trunk if necessary,” declares the indomitable manageress. Nor will she stand any love-making nonsense to interfere with the work in what she calls her “Adamless Eden.”

“No, my doorkeeper won’t flirt with the men. She is a fine, handsome woman with grey hair, inexpressibly dignified, and no man will take liberties with her. At least, I pity the one that tries.”

Man will not be entirely banished from the Company. He will be suffered to play the male roles, but otherwise will be quite subordinate. Listen to this strike-loving scene-shifter of the sterner sex!

“I expect to get a cleaner production by reason of my woman stage director. A woman is naturally artistic. She will not take more time to set the stage than a man, but it will be done infinitely better.

“My artists would fall down every night if I did not go after the men and smooth the wrinkles out of the carpet. A woman would never do such clumsy work.”

Miss Haynes’ final word breathes the very spirit of determination. “I have always come off ahead in our battles, and I’m sure that my new venture of an Adamless troupe will succeed.”

This article and images were originally printed in The Bystander, No. 98, Vol 8, Wednesday, October 18, 1905.