We just finished our summer season in Central Park with a theatricalized concert version of “Capeman”, the musical by Paul Simon. Though it got less-than-stellar reviews the first time around (and cost $11 million for 68 performances), this reincarnation was very well-received and quite enjoyable. It was also a lot of fun to work on, sort of like a chaser to the stomach-churning intensity of the two Shakespeare shows in repertory we did at the beginning of the summer (though having one of them transfer to Broadway is a nice feather in the cap). Plus, production meetings at the end of a long day of tech become a lot more fun when Paul Simon is giving you notes.

Anyway, the show had a few paper props I made; these are two of them, one of which made it in, the other which was cut. If you’re unfamiliar with the story, here’s a quick summary so you can follow along. “Capeman” is a fictionalized retelling of a real event. In 1959, Â during a gang fight in Hell’s Kitchen (a New York City neighborhood), a 15-year old named Salvador Agron stabbed and killed two teenagers. He wore a cape, hence the nickname; the story exploded in the news media. He was convicted and placed on death row, but his sentence was lessened to life in prison. The musical follows his early life in Puerto Rico, the stabbing, his imprisonment, and his search for redemption and salvation while in prison.

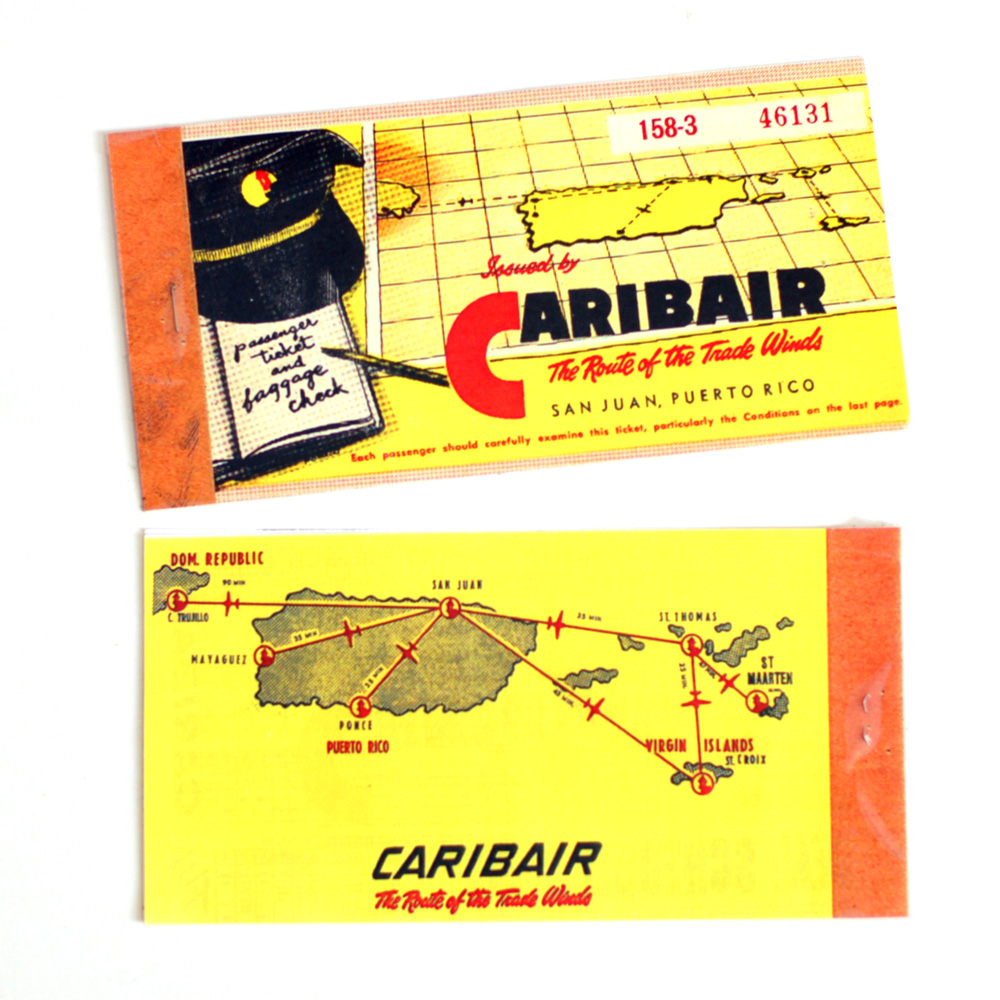

The airline ticket is given to Agron’s mother while they lived in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, by a New York preacher who wishes to marry her. As the show is based on a real event within the last century, I was able to dig up a lot of historical information and primary sources right on the internet. Several sites in particular came in handy. Airline History has a database showing which airlines were operational in different parts of the world throughout the history of aviation. They also have a lot of images of airline tickets. The front cover is an early 1950s ticket from Caribair, an airline that flew out of Mayagüez during the time period of the show. I liked the artwork of it, so I copied it “as is”. I resized it to the size of a typical airline ticket at that time, which I found by looking at several 1950s airline tickets on eBay that listed dimensions in their descriptions.

Airline Timetable Images was another great site I used. Though they cover timetables throughout history, rather than tickets, the artwork is still the same. This is where I found the back cover for my ticket shown above. I resized it and changed the colors to match the front cover. Airtimes is another great source for these kinds of images and information.

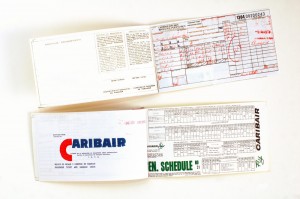

These are the inside pages. I made these from bits and pieces of ticket images I found from the previously mentioned sites, as well as eBay. It’s always a little harder to find images of the boring parts of ephemera, since most sites only scan and display the fun colorful parts. Also, the actual ticket part is taken by the airlines which tend to throw them away, as opposed to the traveler who is more likely to keep it as a souvenir. I’ve never even bought a real paper airplane ticket in all the times I’ve flown, so I couldn’t use my own memories as a reference.

I think what I came up with was close enough, particularly since they never display the inside of the ticket to the audience. I even remembered to check which airports existed in New York City at this time period; she couldn’t very well have a ticket in 1953 from Mayagüez to JFK!

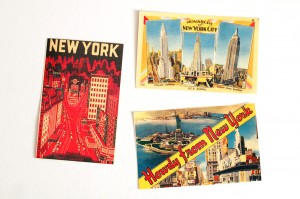

I also made some postcards. I made three, but they were only going to use one. I thought these three were different enough to give them some choices. I really liked the red one on the right, as it reminded me of “West Side Story”, which was happening during this same time period and which dealt with some of the same issues and locations as the real Capeman saga. During rehearsal, they decided to change the postcard to a letter in an envelope.

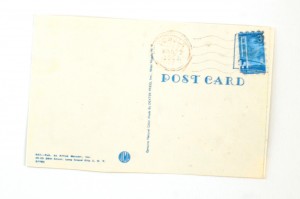

I found an image of the back of a postcard from this time period as well. I printed the stamp image out separately and cut it out with those craft scissors that give you a wavy edge. Jay has several postal ink stamps in his tool bag, so we finished this off with a cancellation mark and a date stamp. It’s the little details like that which add so much more depth to a paper prop without adding too much effort.