Last week we were looking at the very first dragon used at the Metropolitan Opera for Wagner’s Siegfried. It was taken care of by the property master there, known only as Bradwell. Who was Bradwell? I found another article from 1891 which gave a bit more information about this man:

“Then Mr. Hay, the executive lieutenant of Director Stanton, turns us over to Mr. Bradwell, the veteran property-master. Mr. Bradwell is from the Drury Lane Opera House, London, and his family have been identified with the property profession for nearly two hundred years. It is a very responsible post, for the whole ‘setting’ and ‘business’ of every performance depends upon the resources of the property department. The ‘properties’ of nearly half a hundred operas, stowed away in rooms, vaults, and racks all over the house, form a more bewildering chaos than the most disordered mind could conceive.”

The article also gives us some information about the Met at this time. This is before the opera moved to its current location in Lincoln Center. “At the right, or Thirty-ninth Street side, on the various floors, are the director’s office, the principal artists’ dressing-rooms, those of the male chorus, the offices of the various heads of departments, music library, property carpenter-shop, papier-maché-rooms, armor-rooms, etc. On the left, or Fortieth Street side, are the greenroom, the main scene-room, the property-master’s offices and store-rooms, dressing-rooms of the female chorus and ballet, and various work-rooms devoted to the manufacture of costumes and stage properties of every description, from a twenty-foot dragon, down to the flower which Marguerite pulls to pieces in the garden scene of ‘Faust.'”

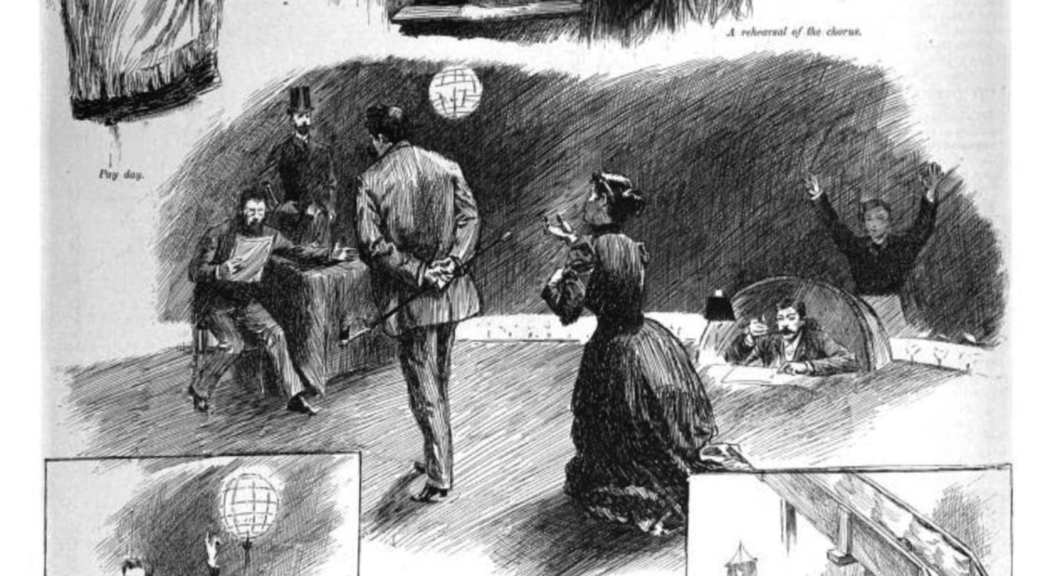

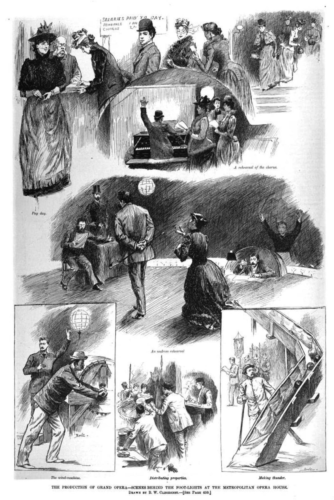

The article also features a very well-done collage illustrating several backstage scenes:

Tyrrell, Henry. “Grand Opera at the Metropolitan.†Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 17 Jan. 1891, pp. 459–460. Google Books, books.google.com/books?id=f8IrAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA459#v=onepage&q&f=false.