Yesterday at Wingspace Theatrical Design I attended their salon on “Being Green.” The featured guests included set designer Donyale Werle (Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, Broke-ology), as well as Annie Jacobs and Jenny Stanjeski from Showman Fabricators.

A lot of the facts which were presented are better summed up in my post on a previous workshop I attended called “Going Green in Theatrical Design.” I did see something that was new though (new to me, that is): UC Berkeley’s Material and Chemical Handbook which presents some of the materials we commonly use in prop making, along with disposal instructions and safety notices. It’s specific to their college, but it is a good starting point for developing your own.

Since I didn’t take notes, what follows is more of a highlight of various points made in the discussion as I remember them:

“Being green is not black or white”; it is not an either/or proposition. Rather, every day you try to make better choices, and every show you try to do a little greener. It takes a lot of experimentation, a lot of analysis, and a lot of effort.

Do not do bad “green” design and art; it’s worse than no design. The goal is to make good design, and the goal of sustainable theatre is to do it a little greener each time.

As theatre people, we already come from a culture of sustainability and recycling. We reuse and repaint flats and drops. We take the lumber from one show and use it on the next. We borrow and barter the costumes and props from other people doing the same. But as our careers progress and the shows get bigger, we get away from that. Maybe it’s because you get to work with bigger budgets, or maybe it’s because you want to push your work to have higher production standards. Making sustainable theatre is a conscious choice and takes a concerted effort.

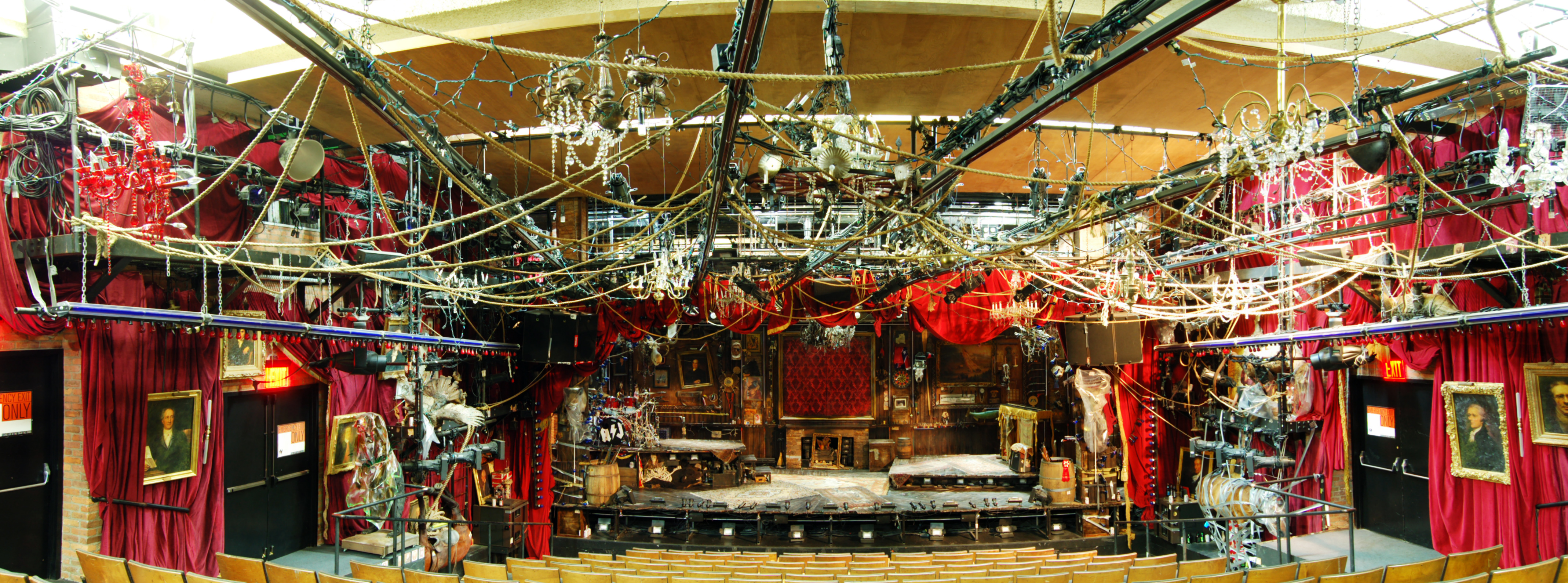

One of the problems, someone pointed out, was in trying to do a green production with a designer who was still in the old mindset—the mindset that everything has to be new and bought just for that show. What is the new mindset? It may mean a design which evolves from the available materials, rather than a design which starts on paper and then requires the purchasing of all new materials. Maybe it just means less design, though as Donyale pointed out, she likes a lot of “stuff” in her designs:

Thinking about more sustainable options means taking more time out of your already busy schedule, and asking others to take more time as well. Donyale pointed out that if you can do case studies on what you’re spending versus what you would spend in a more traditional production, you can convince the producers; for Peter and the Starcatcher, she calculated that they saved $40000 in materials by using recycled, salvaged and upcycled materials, but that the labor cost was a third more due to all the sourcing and processing of this material. Still, it was an overall savings; the extra labor cost was offset by the reduced materials cost. Producers like to see savings. It is also, for a lot of us, morally preferable to have more of the money to go to human labor (which is sustainable) than to the purchase of materials shipped from across the globe which will end up in the trash once the show is finished.

For artisans and production people, as opposed to designers, using more sustainable techniques means taking time to do your own experimentation and comparison of materials and techniques to arrive at better solutions. If you can come up with concrete alternatives to show your designers, it becomes easier to convince them to trust you. An example the ladies from Showman gave was using carved homasote, which is made from recycled newspaper and non-VOC adhesives, to make faux brick and stone facades, rather than vacuum-formed plastic panels. Not only is the plastic a petroleum-based product shipped from overseas, but it releases toxic fumes when heated in the vacuum former. Homasote comes from a company in New Jersey, so it only has to travel a few miles. The results look the same, and the costs are comparable. By showing the designers what they can achieve with more sustainable and less toxic materials, it makes it easier to convince them to accept them.