[The following is an account of a truly extravagant production of Cinderella in Paris, 1866. The amount of people involved feels more like a blockbuster film than a theatrical production; these féerie, a mixture of dance, melodrama, and spectacle, were indeed the blockbusters of their time.

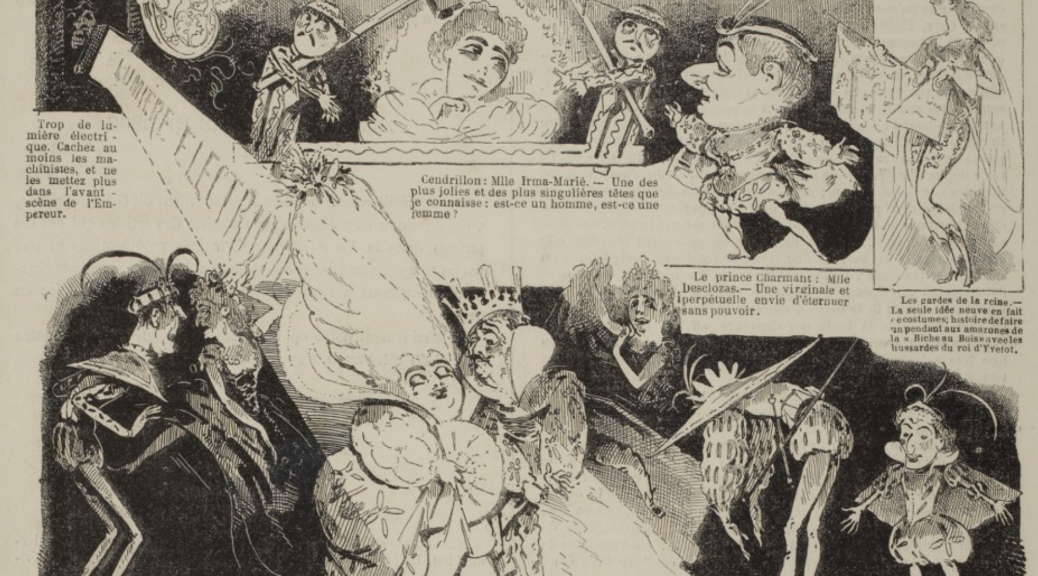

Gallica, the National Library of France, has a number of images and drawings related to this production.]

There was recently brought out at the Theatre du Chatelet in Paris, in the most splendid style, a fairy piece founded on “Cinderella.” It contains thirty-two tableaux, and there are no less than six hundred and fifty different costumes seen in the course of the play; the ballet is danced by the Princesses of the Stars, and the Princesses of the Island of Flowers, the Princesses of the Island of Butterflies, the Princesses of the Crystal Grottoes, the Princesses of the Island of Volcanoes, the Princesses of the Diamond Mines; the final apotheosis changes four times. Nothing so splendid was ever seen in Paris. Enormous sums of money were spent on it. There are seven hundred people employed every night in connection with the piece, namely:

One head machinist, five head gas men, five electric light men, five costumers, five seamstresses, five shoemakers, five property men, five magazine men, five armorers, one head stage manager, four deputy stage managers, seventy-six machinists, forty gas men, eighteen dressing men, eighteen dressing women, twenty call boys, two hundred and ninety-seven female figurantes, thirty-four danseuses, twelve infant danseuses, and twenty-four actors and actresses; total, seven hundred and eleven persons. During the three months preceding this performance, sixty women and men were at work making the six hundred and fifty costumes worn in the piece; for six months before it was played forty-two carpenters, blacksmiths, locksmiths, etc., were employed making the machines and scenes. The dry goods bill for silk and golden goods bought in London and Lyons is $13,000; the stocking, net cost, $3650; the embroidery, $4000; the ornaments (made by Granger), $1880; the shoes, $2020; the bonnets, etc., $1500; flowers, $1220; belts, $460; diamond shields, $580; armor, helmets, etc., $840; feathers, $560; pasteboard, $480; “property,” $2140 – total, $31,200. Add the scenery, drapery and mirrors used, which cost above $20,000, but say only $10,000 – total $51,200. The daily expenses are $420. It is reckoned the piece will run three hundred nights at least, and take between $2000 and $2200 a night. The expenses, including $60,000 original outlay, will be $186,000 for three hundred nights; the receipts will be between $600,000 and $660,000, leaving in the manager’s hands between $404,000 and $465 – a prize worth struggling for.

Public ledger. [volume 3] (Memphis, Tenn.), 18 Sept. 1866. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85033673/1866-09-18/ed-1/seq-1/>