The following is an excerpt from “The Theatre Through its Stage Door”, written by David Belasco, and published in 1919.

During all the time that rehearsals have been in progress—and perhaps for many weeks or even months before the first reading—other preparations for the production have been going on. Carpenters have been building the scenery in my shop, artists have been painting it at their studios, electricians have been making the paraphernalia for the lighting effects, property men have been manufacturing or buying the various objects needed in their department, and costumers and wig-makers have been at work. All these adjuncts to the play have been timed to be ready when they are needed. At last comes the order to put them together. Then for three or four days my stage resembles a house in process of being furnished. Confusion reigns supreme with carpenters putting on door-knobs, decorators hanging draperies, workmen laying carpets and rugs, and furniture men taking measurements.

Everything has been selected by me in advance. My explorations in search of stage equipment are really the most interesting parts of my work. I attend auction sales and haunt antique-shops, hunting for the things I want. I rummage in stores in the richest as well as in the poorest sections of New York. Many of the properties must be especially made, and it has even happened that I have been compelled to send agents abroad to find exactly the things I need. For instance, I sent an agent to Bath, England, to buy all the principal properties for “Sweet Kitty Bellairs.” It was necessary, also, to send to Paris to obtain many of the objects which fitted into the period of “Du Barry.” I purchased the old Dutch furniture I used in “The Return of Peter Grimm” fully two years before I had put the finishing touches on the writing of that play, and most of the Oriental paraphernalia of “The Darling of the Gods” I imported direct from Japan.

When I produced “The Easiest Way” I found myself in a dilemma. I planned one of its scenes to be an exact counterpart of a little hall bedroom in a cheap theatrical boarding-house in New York. We tried to build the scene in my shops, but, somehow, we could not make it look shabby enough. So I went to the meanest theatrical lodging-house I could find in the Tenderloin district and bought the entire interior of one of its most dilapidated rooms—patched furniture, thread-bare carpet, tarnished and broken gas fixtures, tumble-down cupboards, dingy doors and window-casings, and even the faded paper on the walls. The landlady regarded me with amazement when I offered to replace them with new furnishings.

While the scenery and properties are being put together I lurk around with my note-book in hand, studying the stage, watching for defects in color harmonies, and endeavoring to make every scene conform to the characteristics of the people who are supposed to inhabit them. However great the precaution I may have observed, I generally decide to make many more changes. Then, when the stage is furnished to my satisfaction, I bring my company up from the reading-room and introduce them to thme scenes and surroundings in which they are to live in the play.

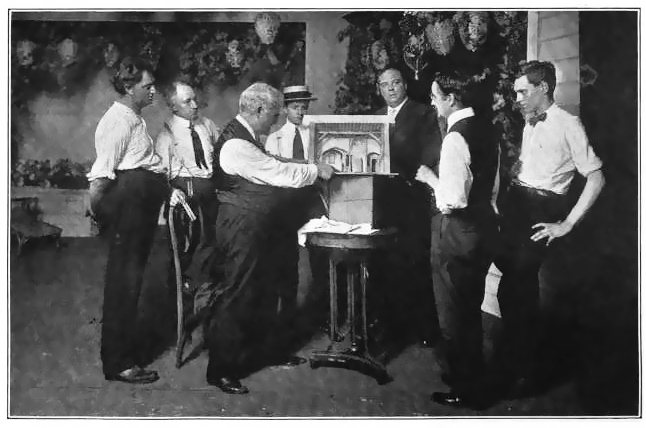

In the above photograph, “they are building a miniature stage-setting of the play, ‘Marie-Odile.’ Every stage-setting used at the Belasco Theatre is built from an exact miniature model which is fully equipped, even to the lighting.”

Text and photograph originally published in “The Theatre Through its Stage Door”, written by David Belasco, and published in 1919.