The following comes from an 1890 news article in the San Francisco Morning Call. You can also check out the first part, the second part and the third part:

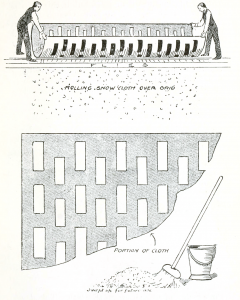

More ingenious is the cleverness employed to depict other accessories to a complete dramatic production. As pretty a stage snow-storm as one would wish to witness happens in “The Two Orphans.” The material for this display was formerly fine-cut paper, prepared by book-binders; in its place white kid in equally small pieces is utilized at present for such purposes.

They can be gathered up more readily, and last longer than paper; besides, there is an ultimate saving in cost. Salt hangs with a better effect to a hat or coat, and gives a thoroughly realistic look to the character that has just stepped indoors from a storm.

If a flash of lightening is needed, the effect is generally gained where electric lights are burned, by rapidly switching the current.

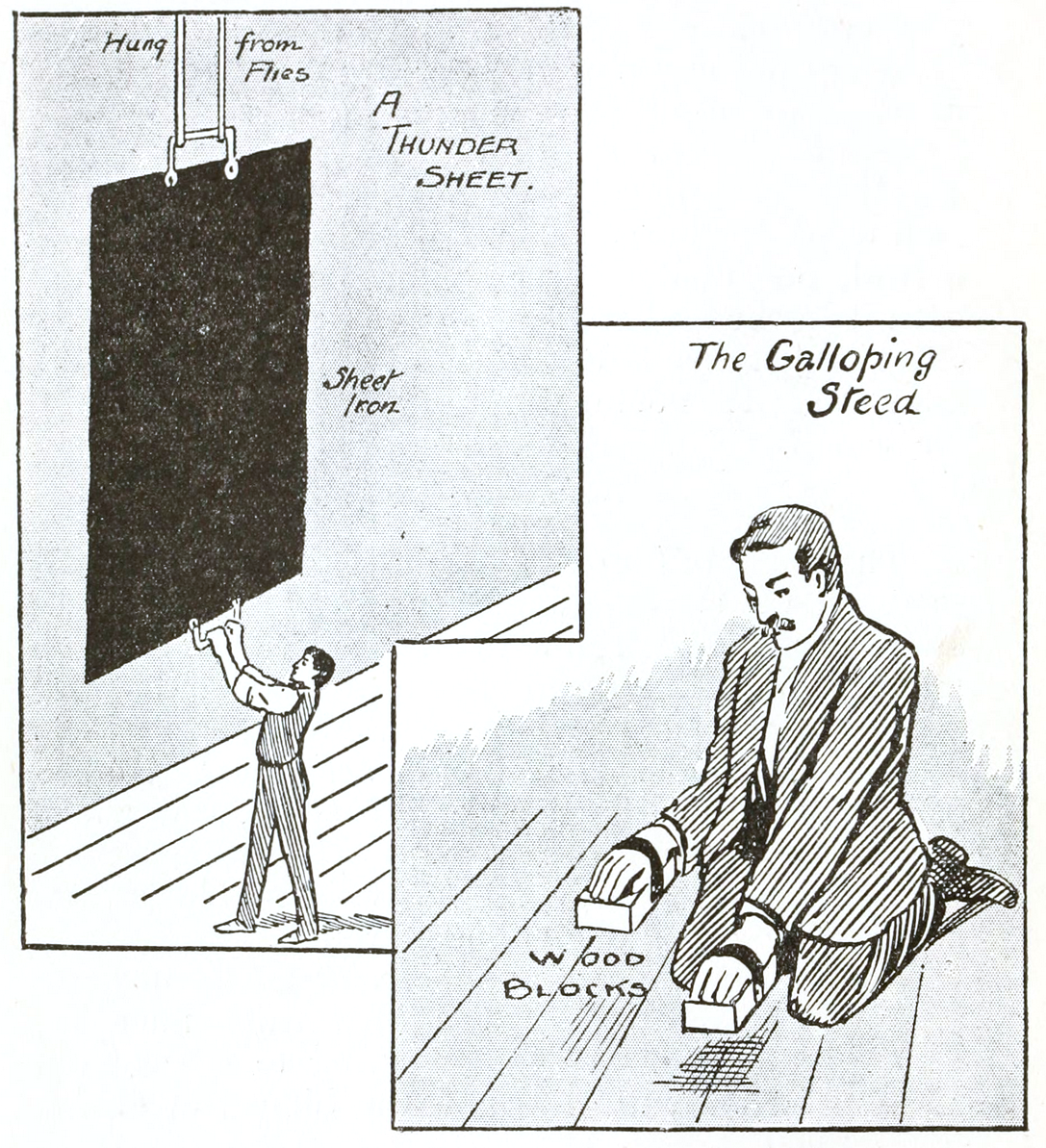

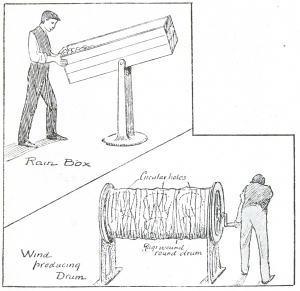

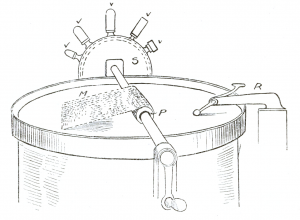

The time-honored scheme is to flash a torch of alcohol, rosin or lycopodium. Stage thunder is the rustling of a sheet of iron suspended from a rafter and set into noisy motion by a long handle. The mighty peals of thunder recently heard in the “Silver Falls” at the Boston Theater were created by a new device, the beating of a huge drum about thrice the size of an ordinary bass drum. This ingenious contrivance gives more distance to the sound. Iron switches bunched like a broom wisp when beaten together will give forth the limitation of rain or hail dropping.

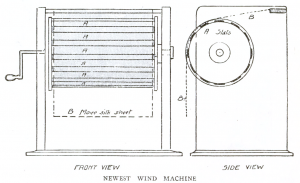

In the “White Slave” water is utilized. The howling wind comes from a wheel that forces the air violently through a large tin funnel with a whistle at the smaller end.

The audience shivers at it, but it may have only been the ancient “wind” the property man makes by drawing his thumb and index finger down a rosined string running through a hole in a tin box such as mustard is packed in. That is the trick of the wind in “Davy Crockett” when the wolves are howling at the cabin door.

Tempest-tossed waves and their white caps that meet the eye of the liberated Count of Monte Cristo as he stands on an ocean rock beyond the Chateau d’If and announces with Georgian assurance “This world is mine,” are but a few bags of saltpeter or a plain salt tossed on a green cloth against a scene.

The mighty motion of the sea that awes the gallery gods who have “Romany Rye” on the brain comprises the united efforts of four men, two on either side of the stage, who shake a length of emerald baize known as a “sea cloth.”

Published in The Morning Call, San Francisco, December 25, 1890, pg 19. Originally written by Felix Barnley in 1887.