IATSE Local 44 has a great list of the various department which fall under “props”. Their descriptions of the different crafts also include the expected set of tools one should show up to work with. Their website used to list the tools required for a propmaker, which I have listed below:

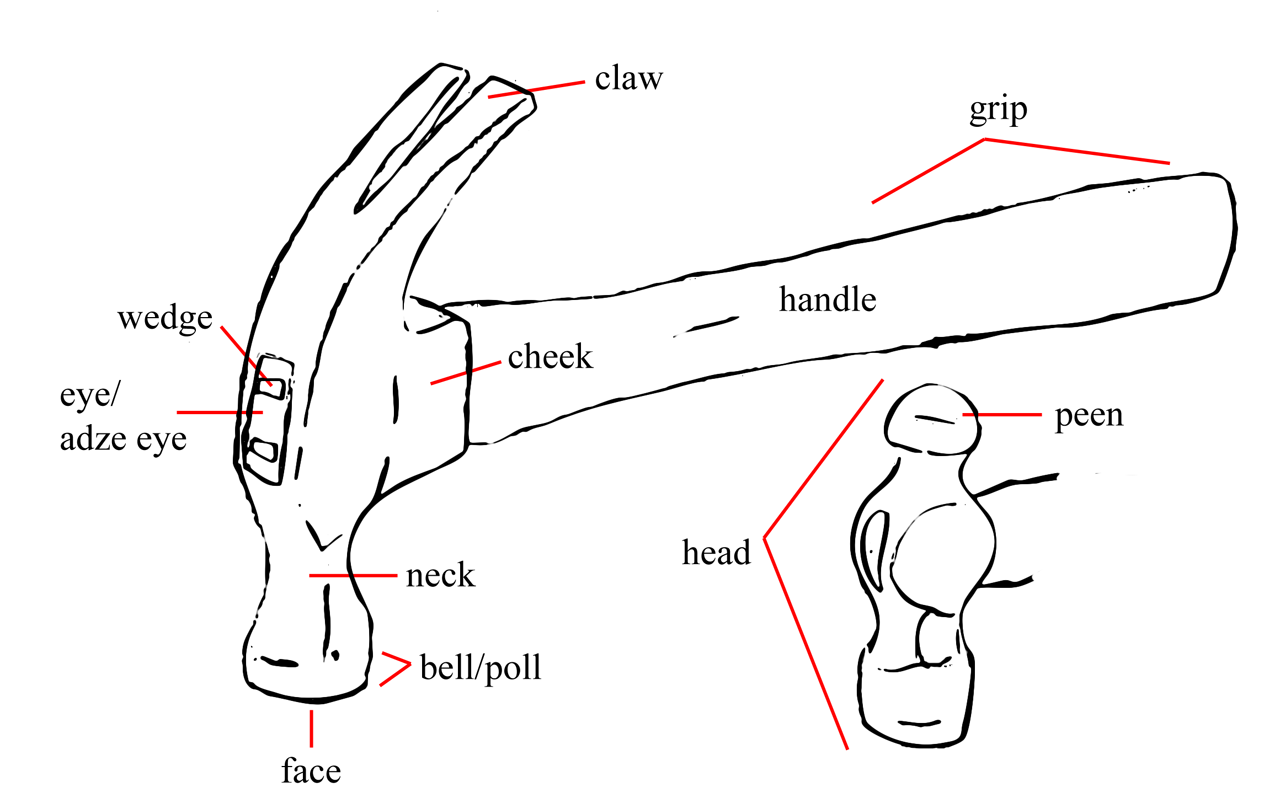

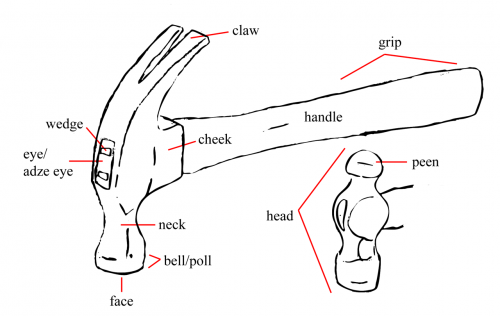

- 16 oz. Claw Hammer

- 25′ or 30′ Measuring Tape

- 100′ Measuring Tape

- 12″ Combination Square

- Framing Square

- Bevel Square

- 8 pt. Hand Saw

- 12 pt. Hand Saw

- Back Saw

- Key Hole Saw

- 1/4″ – 1/2″ – 3/4″ – 1″ Wood Chisels

- Cold Chisel

- Box Plane

- Hand Axe

- Two Chalk Boxes

- Dry Line

- Line Level

- 24″ or 30″ Level

- Compass

- Angle Dividers

- 24″ or 30″ Wrecking Bar

- 10″ Vise Grip Pliers

- Pliers

- Diagonal Cutters

- Straight-head and Phillips-head Screwdrivers

- 10″ Crescent Wrench

- Nail Sets – Various Sizes

- Wood Files – Various Types and Sizes

- Sharpening Stone

- Tool Belt

- Assorted Pencils and Marking Crayons

- Plumb Bob

- Utility Knife and Blades

- Gloves

- Cordless Drill

- Large Ratcheting Screwdriver (Yankee)

- Tool Box

IATSE Local 44 is also known as the Affiliated Property Craftspersons Local 44; it covers workers in film, TV and independent shops in Los Angeles (though members work throughout the world). As such, the above list is specific to those employees. Still, it is a good starting point for propmakers in other situations, locations and fields. My own traveling prop kit includes some tools I can’t live without, and does not include some of the tools listed above. What does yours look like?

As a postscript, you will notice the list contains no tools for soft goods, sewing or upholstering. This is not an oversight; rather, these crafts are separate departments in the local, and thus have their own list of expected tools detailed on the website, which I may write about in the future.