A while back, I wrote about how props may have been acquired and used in the theatre of the ancient Greeks. Since then, I’ve found some more out.

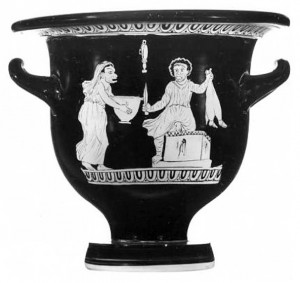

This vase shows Telephus threatening Orestes. Though several Ancient Greek plays dramatize this scene, modern scholars believe this vase depicts Aristophanes’ parody of Euripides’ version. More importantly, this vase is one of the rare examples of an illustration of an actual theatrical performance. Â We see the “baby” which is held is actually a wine skin with Persian booties tied on the bottom. It is filled with wine so it could “bleed” as it is cut open.

Note this is not a “special effect”, at least in this context. In the play, Mnesilochus believes he is about to kill a baby, but as he unwraps its clothing, he realizes it is actually a wine skin. As the play is a parody, this may actually be describing a well-known prop trick. Our modern comedies have many examples of when a character realizes he or she is actually in a movie (or play) and the objects being used are merely “props”, ie cheap or poorly-made imitations.

The following comes from The Attic theatre: a description of the stage and theatre of the Athenians, and of the dramatic performances at Athens. The first quote speaks of statues. In some theatres, statues actually fall under the oversight of the scenic artists, but they can be the responsibility of the props department as well.

In addition to the scenery in the background the stage was of course decorated with such objects and properties as were required by the particular play. Aeschylus is said to have been the first to adorn the stage in this manner (Vit. Aesch. p. 6 Dindf.). If the scene was a palace or a temple, statues of the gods were generally placed in front of it, and are frequently referred to in the course of the drama. For instance there was the statue of Athene in front of her temple in the Eumenides, and the statues of the tutelary deities before the palace of the Atreidae in the Electra of Sophocles. In the Hippolytus there were two statues in front of the palace of Theseus, one of Artemis the huntress, and the other of Cypris the goddess of love. When Hippolytus returns from the hunt, he offers a garland of flowers to the statue of Artemis, but refuses to pay the slightest homage to the statue of Cypris, in spite of the remonstrances of his attendant. Again, in the country region depicted in the Oedipus Coloneus the statue of the hero Colonus stood in a conspicuous position (Aesch. Eum. 242; Soph. Electr. 1373, O.C. 59; Eur. Hipp. 70–106.). Other examples of the practice of decorating the stage with statues are frequently to be met with both in tragedy and in comedy.

The book next speaks of altars, obelisks, tombs and benches. Again, these items may fall under other departments, such as scenery. The point is not to quibble over the “prop-iness” of these objects, but rather to provide a catalog of the various objects which may have been found in an Ancient Greek production.

Altars again were very common objects upon the Greek stage. In the Supplices of Aeschylus the fugitive maidens take refuge round an altar. The Oedipus Tyrannus opens with the spectacle of a group of Thebans kneeling in supplication before the altar of Apollo (Aesch. Suppl. 188–200; Soph. O.R. 1–3, 142.). Another very ordinary feature in the stage-decoration was the stone obelisk in honour of Apollo of the Highways. It was an ordinary practice among the Greeks to place such obelisks in front of their houses. Their presence upon the stage is frequently referred to both in tragedy and in comedy (Poll.iv. 123; Aesch. Agam. 1080 ff.; Schol. Eur. Phoen. 631; Arist. Vesp. 875.). Various other objects were occasionally required by particular plays. There was the tomb of Darius in front of the palace of Xerxes in the Persae, and the tomb of Agamemnon in front of the palace of the Atreidae in the Choephori. In the Oedipus Coloneus a rocky ledge was required for Oedipus to rest himself upon. In the Acharnians and the Knights a few benches must have been erected upon the stage to serve as a rude imitation of the Pnyx. Walls, watch-towers, and beacon-towers are mentioned by Pollux; and the presence of other similar decorations and erections can be inferred from the extant tragedies and comedies (Aesch. Pers. 684. Choeph. 4; Soph. O.C. 19; Poll. iv. 127.).

Finally, this text discusses chariots and animals. I’ve given my opinion about whether an animal is a prop or not; a chariot, on the other hand, most certainly is.

There was one piece of realism which the Greeks were not averse to, and that was the presence of horses and chariots upon the stage. There are many instances in tragedy of per sons from a distance arriving in a chariot drawn by horses or mules. The vast size of the Greek theatre, and the length and narrowness of the stage, made it peculiarly suitable for displays of this character. In the Agamemnon of Aeschylus Agamemnon and Cassandra approach the palace in a chariot; Agamemnon remains seated there for a considerable time, while he converses with Clytaemnestra; he then dismounts and enters the palace, leaving Cassandra still in the chariot. In the Prometheus the chorus of the Oceanidae enter the stage in a car. In the Electra of Euripides, when Clytaemnestra comes to visit her daughter at the country cottage, she arrives in a chariot, accompanied by Trojan maidens, who assist her to dismount. Several other instances might be mentioned. Animals for riding were also introduced upon the stage. In the Prometheus there is the winged steed upon which Prometheus makes his entrance; and finally in the Frogs of Aristophanes Xanthias rides in upon a donkey (Aesch. Agam. 782–1054, Prom. 135, 279, 284; Eur. Elecr. 998, 999; Arist. Ran. 27.).