What is a “prop bible” and why do we have one? We can answer the first question by answering the second; if a prop master were to disappear off the face of the earth during the preparation of a show, the prop bible would allow his or her replacement to pick up exactly where the process was left off. Thus, a prop bible would have any and all information which a prop master has picked up in the course of propping a show about the props and their various details.

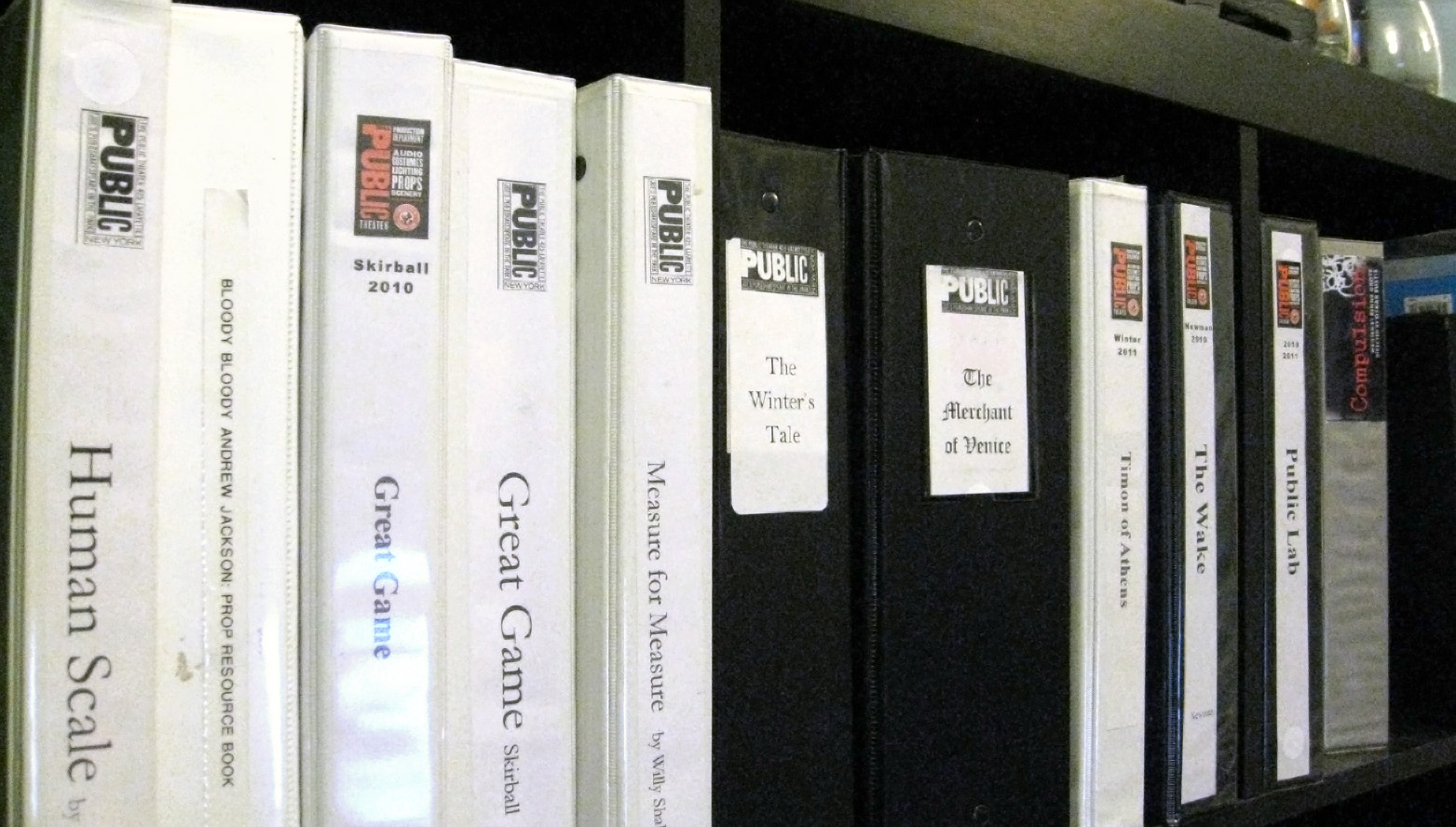

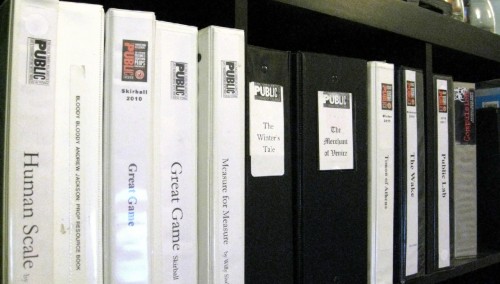

The first thing a prop bible would have is a copy of the script. Like most prop masters, I like to have the script printed on one side of regular copy paper and placed in a three-ring binder. This lets me add notes, highlights, and otherwise mark up the script. It also allows me to write more detailed notes on the opposing blank page.

The next vital item to have in the prop bible is an up-to-date version of the prop list. The subject of what goes in a prop list is a discussion in and of itself. I wrote about how to read a script back in 2009; while it touches on some parts of creating a prop list, I haven’t explicitly written about the process yet. The important thing for the purposes of this article is to have a single document which lists every prop and piece of set dressing that is expected of you.

Next up is all the information the designer gives you. Drawings, draftings, research and inspiration photographs, and even verbal and written descriptions should all be collected as much as humanly possible. You may not be able to fit full drafting plates in your book, but if possible, you can print out or photocopy at reduced size or selected portion of the drafting with an indication that the full-size version exists in another location. I often do my own supplementary research; I indicate that these pictures did not come from the designer or director, as this can sometimes be an important distinction.

The daily rehearsal reports are also integral to a props bible. The stage managers will (hopefully) sum up all the prop notes and discoveries during the day’s rehearsals and send it out to everyone on the production team. This is where many of the notes about the usage and practical requirements of the hand props will come from. When someone asks “Why is Hamlet’s sword so short?”, you can point to the rehearsal report where the actor decided he would hide his sword under his cape, and a longer sword would stick out the bottom.

Other preproduction information to have copies of includes minutes from production meetings and any other meetings with the director, designers, or stage managers. Basically, any communication, written or verbal, where decisions are made about props should be included in the bible so you don’t end up making a fool of yourself by picking out a chair for a show which the director told you weeks ago was not the style he wants.

Your prop bible is also where you want to keep all the other relevant information about your production, such as the contact sheet, schedules, and any contract you may have signed.

As your process gets underway, you need to ensure that your prop bible remains up to date. You can also add information about the sources of where your props come from. If they are borrowed or rented, you can keep contact information for the source. You may also record information about stores or vendors where you buy items from. The actual financial documents, such as receipts and invoices, are not kept in the bible; in most organizations, you need to submit the original copies of these to the accounting department or some similar department. But keeping track of the budget and keeping your budget estimate up-to-date is a good thing to have in the bible. If you were to drop off the face of the earth and someone else had only the prop bible to finish the show with, he or she would want to know how much money was left to spend.

Once the show is “frozen”, you can begin the process of documenting the show. Pictures of every prop are vital, as are pictures of how the set dressing is arranged on stage. Prop preset lists and running sheets from stage management and run crew are good to have, too. If props are arranged a certain way backstage, either on prop tables or on shelves, photographs or even diagrams of these arrangements can also be included. You should list the consumables used during the show, including how much is needed per show or per week. Any sort of food, blood, or other recipe-based prop can have its recipe recorded and instructions on how to prepare it. It is especially helpful to have a pristine copy of every paper prop used, so that new copies can be made; if you have digital versions, you can burn these to a CD to keep with the bible as well. At this point, the prop bible becomes the document with which a person can recreate the props for a production down to the last detail.

In some cases, a theatre actually does remount a production it did in the past, or rent out the props as a complete package to another theatre. Even if your organization does not do that, the prop bible still comes in handy for a number of other reasons. Sometimes you want to track down the vendor of an item in your props stock; looking through old prop bibles can sometimes yield this information. Often, we get artists who remember certain props and want us to track them down. “I remember using a green table when I did Hamlet here in 2004,” a director may reminisce. “Can we get that for our next show?” You may not have worked in that props department back in 2004, but if your predecessor had kept good bibles, it would be a mere matter of looking up that show, finding the photo of the table in the bible, and matching it to an item in your stock. Or, it may reveal that such an item was actually rented in 2004, and you can call the rental place to see if it is available.

The point of all of this is that when wagering against what information you will need in the future, keeping accurate records now will ensure you always win that wager, regardless of the situation.

For more on creating and maintaining a prop bible, I highly recommend Amy Mussman’s book The Prop Master, as well as Sandra Strawn’s The Properties Directors Handbook. You can read that last one for free on the internet, and I have a link to it on my sidebar, so if you haven’t checked it out yet, now’s your chance to see what you’ve been missing.