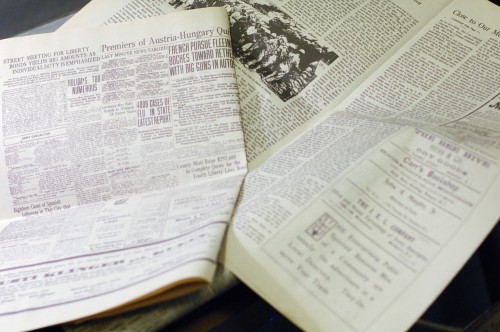

They used to solve this problem in the breakfast scene of “The Duke of Killiekrankie” by having the food made of candy which would melt rapidly in the mouth, and so not interfere with enunciation. The hashed brown potatoes, for example, were nothing but spun sugar, browned, which looked substantial enough to the audience, but melted away almost as soon as they touched the tongue.

– The New York Times, April 1, 1906.

I have previously written about making inedible fake food. A props person may also have to make edible fake food. What is edible fake food? Say a character needs to eat a peanut butter sandwich, but the actress playing that character is allergic to nuts; you need an edible replica of peanut butter that contains no nuts.

Props people make edible replicas for a variety of reasons. Most common is the above-mentioned allergy issue; before planning a meal, you (or your stage manager) needs to find out what the actors are allergic to, and any special dietary needs. An actor may be vegetarian or keeps kosher. Besides allergies and diet, actors avoid other types of food while on stage; milk and cheese, or sugary drinks, tend to affect the vocal chords in ways which many actors dislike. A prop master’s greatest challenge is when he or she needs to serve a massive edible banquet, and an actor is vegetarian, allergic to gluten, and lactose-intolerant.

Another reason to make edible fake food is cost. Characters on stage may chow down on what appears to be hundreds of dollars of caviar in a single scene. You need a more cost-effective solution if you want to keep your budget under control. In a similar vein, certain foods may be time-consuming or complicated to prepare. Remember, your running crew needs to prepare the food before each show in addition to their other pre-show duties, and if your production has matinées, they may have an even tighter schedule between the two shows. It’s usually better to microwave a turkey substitute for thirty seconds than to roast a real turkey for four hours.

Third, the food on stage may require special properties which the real deal does not possess. A common example is when a director wants the characters to eat ice cream, but does not want to see the ice cream melt during the scene. It’s a tricky feat to pull off under those hot stage lights.

Finally, an actor may need to eat something which is normally not edible. Edible flowers are commonly called for, as well as paper notes. Be prepared for anything.

It is important to keep the food preparation area clean, which means separate from any work areas. If you keep a stock of preparation dishes and utensils, these should be kept separate from your regular stock of kitchen props; you don’t want to prepare your food in a dish that was painted with a toxic paint for the previous show. Likewise, the food needs to be stored properly in between shows, especially if you buy a whole bunch at once for multiple performances. It should also go without saying that you should not attempt to reuse uneaten food from one performance for the next one.

Creating edible food is a little bit sculpture, a little bit painting, and a whole lot of creativity. It’s good to develop a sort of “base” of materials which are readily available, easy to work with, and can mimic a great deal of foods. Bananas, breads, and food coloring have been some of the more popular bases for props artisans for well over a century.

Bananas can be mashed to imitate a great number of foods, such as cream or ice cream. With the right coloring and toppings, it can even substitute for meat or fish. When sliced lengthwise, you have a decent white meat substitute for chicken. Yogurt and cottage cheese work in a similar vein, but because of the milk content, they are less-commonly used.

Bread can take on a variety of shapes. Brown bread with the crusts removed and cut to the proper shape can simulate chops and roast meat. I saw the head of properties at the Walnut Street Theatre create a very convincing Salisbury steak each night with just a slice of pumpernickel covered in cold canned gravy. Switch the gravy with fruit glaze or some other red jelly and you have a slab of raw meat. A whole loaf with the crusts removed can be shaped into a number of different forms. If you use a loaf that is at least a day old, you can even carve it somewhat.

Tofu is another kind of base which can be built on for any number of fake edibles. It has the advantage of being vegan, and in some cases, gluten-free, so it’s a great choice for tricky eaters.

Food coloring adds greatly to your repertoire of faux food creation tools. It can be tricky to match the color and opacity of your intended goal; luckily, everything is edible, so you can eat your tests and samples. Specialty baking shops will stock a greater range of colors and sizes, so you don’t have to try to create every single color with those tiny bottles of red, yellow, blue and green. You can also find culinary colors in spray cans, which are a boon for the more artistically inclined.

Fruits are a friendly substitute for many foods, and can be tastier for the actors than old bread covered in cold gravy. I used a fresh grape and a dried apricot for my appetizers in Timon of Athens. I’ve also heard of shows which used half an apricot for an egg yolk and a pared apple for a raw turnip. Watermelon with some brown food coloring makes a convincingly juicy slab of raw meat. Dried fruits such as prunes and apricots can be cut up, shaped and squished to resemble a variety of things, and are especially handy when you have that large banquet scene that requires a variety of edible colors and textures to appear sumptuous.

Sausages and other imperishable meats serve a similar purpose as dried fruits. With the skin removed, they can be sliced and carved to mimic all sorts of appetizers and side dishes.

Fake edible food is a great exercise for students and interns because it forces them to distill an item (the real food) to its most recognizable characteristics, and then come up with a simple and economical replication of those characteristics. It makes them think about the constraints of a show, such as preparation time, cost per show, shopping time, etc. Finally, most people do not create fake food in their spare time, so they can’t fall back on familiar materials and methods, such as carpentry or foam carving.

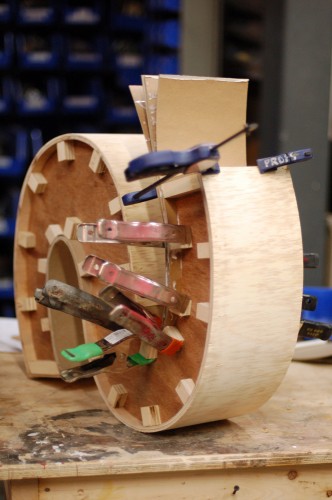

A knowledge of cooking, baking, and food preparation is helpful, as it can help you learn how to thicken or thin various sauces and liquids, or give you clues how to cut and shape different foods. A trip to a culinary or baking store is great as well, as you can find all sorts of icing bags, cookie cutters and food-safe molds to help you out. I read about a production in 1906 which used a mold of a chicken to bake a sponge cake that could be carved and consumed on stage. Now that’s a tasty trick!

It was a very hefty sword and a lot of fun to swing around. One day, I wasn’t paying attention while swinging it around, and I accidentally cut all my facial hair off. And that, my friends, is the secret origin of “Clean-Shaven Eric”.

It was a very hefty sword and a lot of fun to swing around. One day, I wasn’t paying attention while swinging it around, and I accidentally cut all my facial hair off. And that, my friends, is the secret origin of “Clean-Shaven Eric”.