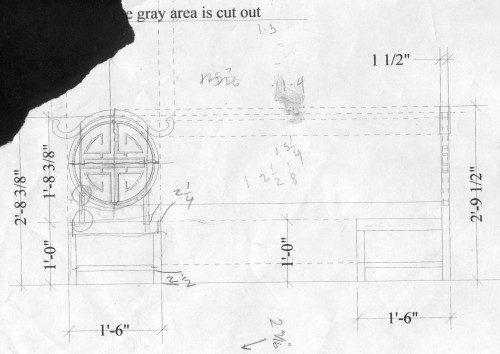

Back in 2007 when I was working at the Santa Fe Opera, we were mounting a new opera called Tea: A Mirror of Soul. It had a heavy Asian influence, with scenes taking place both in Japan and in China. I was given a drawing of a chair, which they needed nine copies of.

If you study the drawing, you’d notice a few things. First, it’s rather small. Normally, a chair is eighteen inches off the ground; this is only twelve. Second, the back stiles for the circular back are offset from the back legs (if you don’t know what a stile is, check out my “parts of a chair” diagram). Â Wooden chairs usually have a single piece of wood running from top to bottom in the back for strength. Where the back meets the seat is the point where a lot of stress is placed on the chair, so relying on the strength of a joint rather than a solid length of wood is inviting trouble. Finally, you may notice that the back has pieces floating in the air. That’s always an engineering challenge.

The seat of the chair was two and a quarter inches thick. I decided to skin the top with a piece of quarter-inch plywood and the bottom with eighth-inch lauan, so the interior frame had to be one and seven-eighths inches thick. That gave me a nice big chunk in the back to attach my back stiles to. I also added some bolts through the joint for extra reinforcement.

The rest of the joints were glued and doweled.

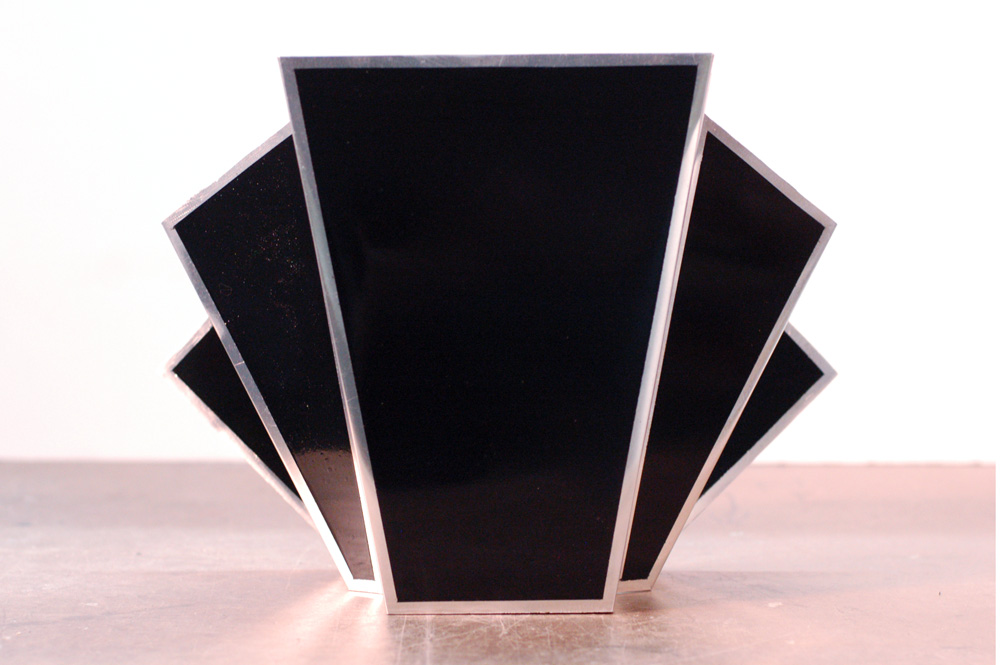

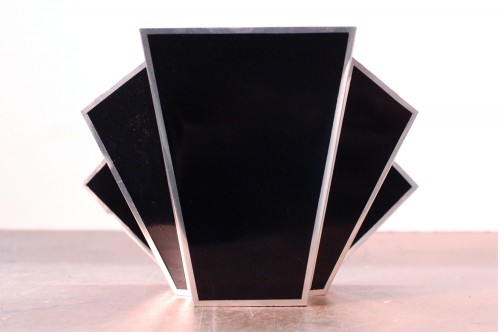

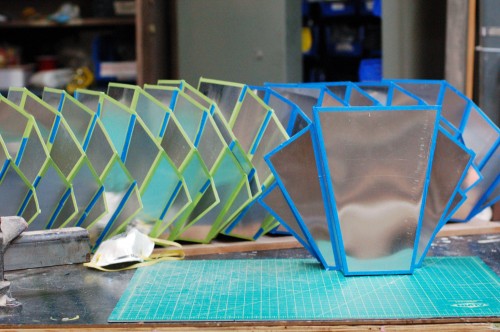

Next came the fun part: the back. We (the props master, master carpenter, and I) needed to figure out a way to make the back pieces appear to be floating. As I mentioned above, I was making nine of these chairs, so the process had to be repeatable as well. The master carpenter was also making a throne with this same cut-out design in it, so he began developing a jig so we could rout the design out of a solid piece of wood. We had discussed using plexiglass in the middle so the pieces would actually look like they were floating, but that would not be strong enough. Instead, we would hide a steel frame inside and have small pieces of steel connecting the pieces. Between the distance of the audience, the sightlines, and the smallness of the gaps, a few pieces of quarter-inch rod steel painted black would be as close to invisible as we could make it.

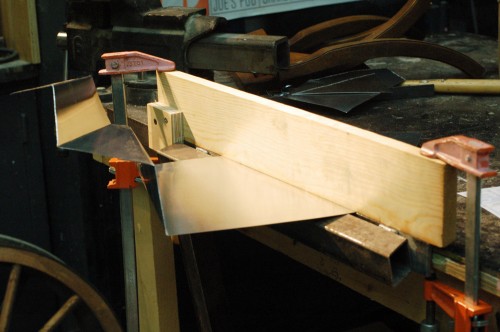

The photograph above shows David Levine, the master carpenter, working out the jig. Note that he’s not actually cutting yet, which is why his dust mask and goggles are off. It was a complicated, multi-piece jig with several steps involved, but the results were beautiful and consistent.

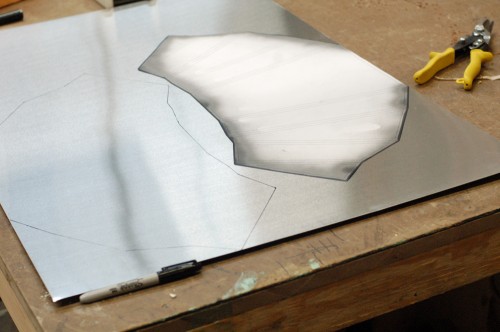

For the back ring, I sandwiched poplar boards on either side of a piece of quarter-inch plywood, with the grain of each side running perpendicularly to the other. In other words, I made a giant Oreo cookie out of poplar, with a creamy plywood center. The interior back pieces were cut out of a solid piece of poplar, Â made by gluing several boards together. I put this in the jig and cut my design out.

Before I had cut out the back pieces, I had routed the channels in where I would hide the steel rod. The channels were as deep as the diameter of the rod, so once they were in, the whole back could get a coat of Bondo and be sanded smooth, and no one would be the wiser. The steel rod continued sown into the stiles and up into the “horn” at the top so the whole back could be tied together with the same steel structure.

I cut the top horn piece out of a solid chunk of poplar, which I made by laminating two boards with their grains running in different directions.

Looking back, even as I write this article, I see a number of things I would do differently, or at least experiment with to see the results. As with any complicated prop, you learn a lot just by building it, but because you will never build the exact same prop again, it can be hard to assimilate that learning into your overall experience. As it turned out with this prop, I had only finished three of the nine chairs by the time they were cut from the show. It seems the stage was getting too cluttered, and the chairs were one of the more extraneous elements, so away they went.

That meant I got to keep two of the chairs, which let me test just how long my construction would actually hold up. The back on one of them did eventually break away from the seat, though not where I thought it would. I contemplated building more of a steel structure, but worried that the extra weight would either make it too heavy to carry, or even make it more likely to break; picture using a crowbar versus a stick of wood. The crowbar is extremely good at separating two pieces of wood from each other, where a stick of wood is just as likely to break itself before pulling the wood apart. Now look at a chair. The point where the back meets the seat is the focal point of a lever formed by somebody leaning back in the chair. If the stiles were metal (like a crowbar), it might tear the seat apart if you leaned back too hard.

But I digress and ruminate too much. Enjoy the pictures of the chair.