I found the following images in a copy of “The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine” from 1900. They appeared in an article about performing Wagner’s Ring Cycle. I love how they give a glimpse of what backstage life was like over a hundred years ago. In most respects, it is very much unchanged from the present form.

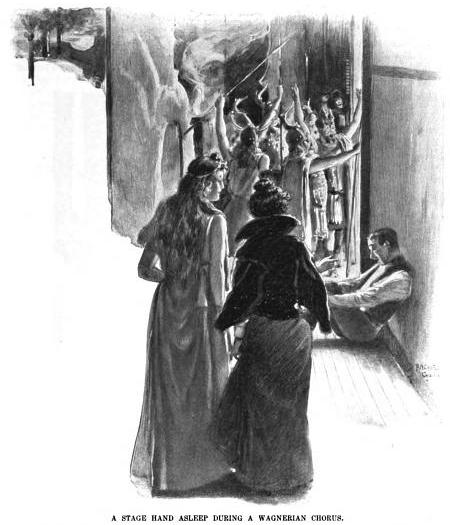

Though asleep, the stage hand above is “better dressed” than the typical stage hand today. Than again, most stage hands need to wear all black clothes, and the fabrics today stand up to much more wear and tear and are easier to clean than the suits and trousers of 1900.

I love the looks of these chorus members as they wait for their moment on stage. What is also interesting is the flat in the background, which is constructed in exactly the same way that modern flats are.

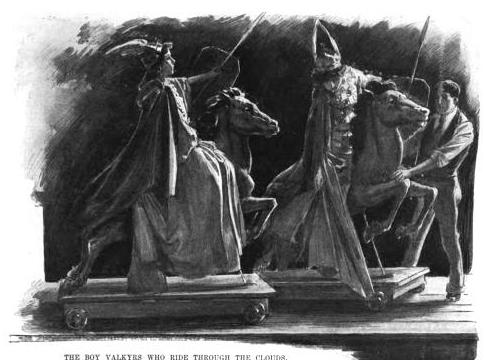

This moving dragon shows a low-tech but reliable solution that is still utilized in all but the highest-budget performances today.

The wagons which carry these boys would not look out of place in a modern opera production. I find it interesting again how the stage hand is dressed; it is not just that he is wearing a vest and tie, but that his shirt appears to be white rather than the dark colors we usually wear back stage.

Finally, this illustration goes to show you that back stage areas have always been cramped.

Images originally appeared in “The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, Volume 59, Richard Watson Gilder, The Century Co, 1900.