The following comes from The Young Woman’s Journal, a self-described “organ of the Young Ladies’ Mutual Improvement Associations”. It was originally published in October, 1921, in Salt Lake City, Utah. I kept in the opening paragraphs so you get a sense of the context which the article was written, then I skipped ahead to the portion dealing specifically with props.

Technique of Play Production

by Maud May Babcock

The community theatre in the days of Brigham Young, was unique. The Latter-day Saints had an organization with such fine ideals and gave performances of such excellence that there has been no equal in theatrical history, and the theatre of Brigham Young stands today the admiration and wonder of the entire world. Have the mighty fallen? We have sold our birthright for a mess of pottage to commercial theatrical enterprise. Instead of leading, showing how communities could entertain themselves and by so doing develop a taste for only the best in music and drama, we are amused by demoralizing vaudeville, and unreal, sentimental “canned” drama. Today our taste is as low as anywhere in the United States. Verily we are what we feed upon! The Mutuals are making splendid effort to help our communities come back to their own and make their own entertainment.

There is a tremendous waste of time and effort in our Ward societies because of the lack of organization, and systematic procedure in our entertainments.

…

Organization in heaven, in the church, in the world spells efficiency. A successful amusement center depends upon its organization. In our dramatic activities, our organization must consist of the following officers:

- Director

- Business Manager

- Stage Manager

- Stage Carpenter

- Property Manager

- Electrician

- Scene Painter

The Director and Business Manager should be very carefully selected by the local Mutual Officers, and these should be responsible to them alone. All the other officers are appointed by the Director and responsible to him or her.

…

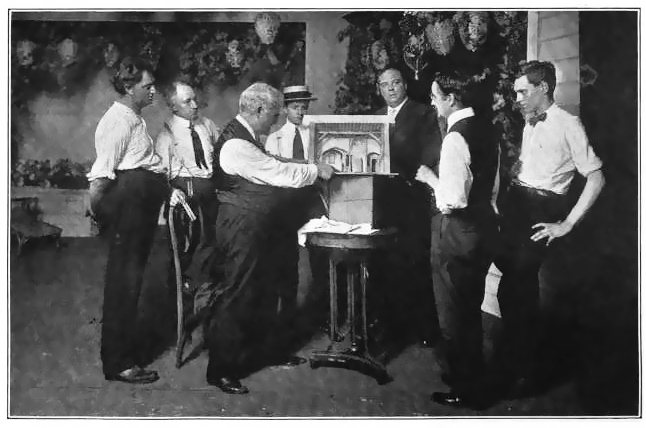

The Property Man—”Props”—provides, cares for, and places in proper position on the stage all furniture, draperies, rugs, carpets, lamps, telephone, letters, documents, etc.—in fact, all articles needed in the play except the personal properties of the actor. Things only used by a single actor—such as a fan, a cane, an eyeglass, a parasol, a handkerchief, a letter, if it remains with the one person and not given to another or is not left on the stage—these are personal “props.” A small table should be provided on either side of the stage for offstage “props,” such articles as are needed to be carried on stage, or for properties brought off stage. The property man should see that actors do not carry such “props” to their dressing rooms, but that they are left on the table provided. Stage drinks—which are made of grape juice, ginger-ale, or root beer, according to the color needed, are cared for and bought by “props” on order of the director countersigned by the business manager.

The property man should take an artistic pride in his stage picture and spend a good deal of time to secure, by renting or borrowing or making, the exact style of furniture and things needed for the play. A period play with modern furniture which one sees in stock performances is ludicrous. Charlie Millard, the veteran property man of the Salt Lake Theatre made all his properties and furnished the actors in Brigham Young’s time with even personal “props.” The stage manager furnishes “props” with a property plot containing a list of properties needed for each scene in the play.

This article first appeared in “The Young Woman’s Journal”, October, 1921.