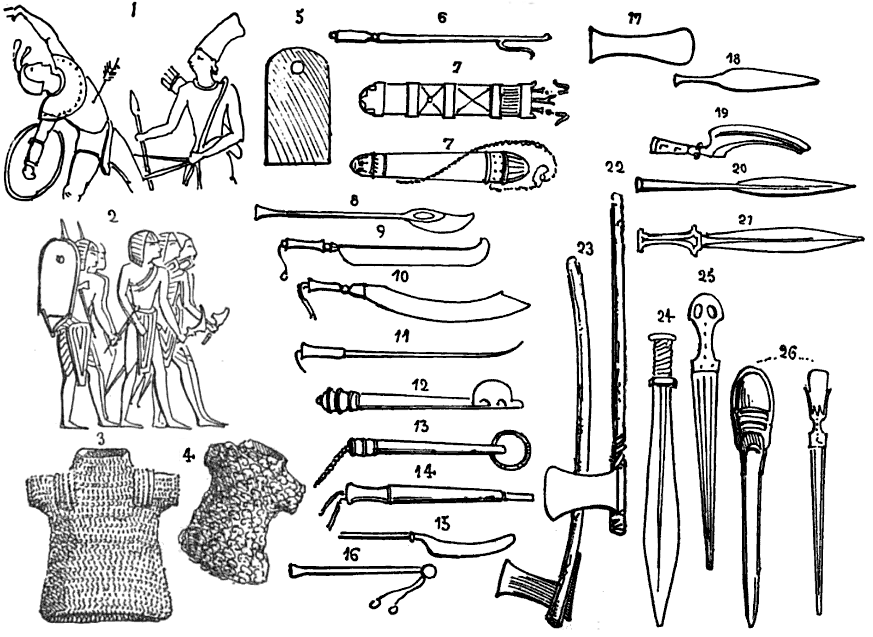

I came across a book with some fun little illustrations showing the history of arms and armor through history. The pictures are not terribly detailed, but they give a good overall look at the shapes and styles of common weapons in various historical periods. The first one I’ll be showing is on Egyptian weapons.

1. A mural painting of Thebes showing Egyptians fighting.

2. Egyptian soldiers from Theban bas-reliefs.

3. Egyptian coat of mail. Some coats which have survived to the present have bronze scales, each scale measuring an inch and a half tall by three-fourths of an inch wide.

4. Egyptian coat in crocodile’s skin. From the Egyptian Museum of the Belvedere, Vienna.

5. Egyptian buckler with sight-hole.

6. Sword-breaker

7. Egyptian quiver

8. Egyptian hatchet

9. Sword

10. Scimitar

11. Dart

12. Sling

13. Unknown weapon

14. Unknown weapon

15. Hatchet, from bas-reliefs of

Thebes.

16. Scorpion or whip-goad. These were most likely 25 to 27 inches long. They were probably in bronze and iron.

17. Egyptian wedge or hatchet, bronze (4 inches). From the Museum of Berlin.

18. Egyptian knife or lance-head, iron (6 inches). Also from the Museum of Berlin.

19. Shop or khop, an Egyptian iron weapon (6 inches). Museum of Berlin.

20. Egyptian lance-head, bronze (10 and a half inches). Louvre.

21. Egyptian poignard, bronze. The handle is fixed upon a wooden core.

22. Egyptian hatchet, bronze, bound with thongs to a wooden handle of 15 and a half inches. British Museum.

23. Egyptian hatchet, bronze (4 and a half inches), fixed into wooden handle of 16 and a half inches. Louvre.

24. Bronze dagger (14 inches). Louvre.

25. Egyptian poignard, bronze (11 and a half inches), found at Thebes. The handle is in horn.

26. Egyptian poignard and sheath, bronze, 1 foot long. Ivory handle, ornamented with studs in gilded bronze.

The illustrations and descriptions have been taken from An Illustrated History of Arms and Armour: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time, by Auguste Demmin, and translated by Charles Christopher Black. Published in 1894 by George Bell.