In 1888, Scribner’s Magazine published a wonderful article called “Behind the Scenes of an Opera-House”. The author, Gustav Kobbé, visits the backstage areas of the Metropolitan Opera. He describes the various shops and workers who create an opera, from conception to opening night. It is one of the most fantastic and detailed looks at the practical construction of a theatrical production I’ve run across from this time period, and so I am presenting all of the relevant parts on properties in their entirety. As the article is quite long, I’ve broken it up to run over the next few days; this will also allow me to take a break from writing during the Thanksgiving holiday. Enjoy!

Behind the Scenes of an Opera-House, by Gustav Kobbé.

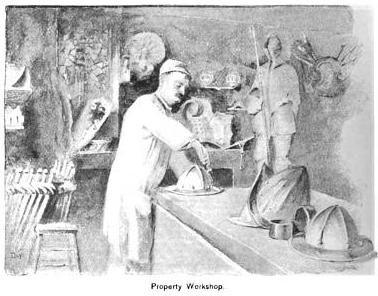

The regions in which the labor of preparing a musico-dramatic work for production goes on are a veritable bee-hive of activity. They embrace, besides the rooms of the heads of the various departments—musical conductor, stage-manager, scenic artist, costumer, property-master, gas-engineer, and master carpenter—those in which their ideas are materialized. Connected, for instance, with the property department is a modelling-room, a casting-room, two rooms in which such properties as flowers, grass-mats, and birds are manufactured, two armories, and three or four apartments in which properties are stored—but this is taking the reader a little too far behind the footlights for the present.

…

Some idea of the labor this involves may be formed from the statement that at the Metropolitan Opera-House it took from August, 1887, until January, 1888, to mobilize this host for the conquest of Mexico under “Ferdinand Cortez,” [Eric: an opera by Gaspare Spontini]Â a period of about the same length as that usually consumed at large opera-houses in preparing a work for production. On the 1st of August, 1887, the managing director handed the libretto to the members of his staff. They immediately set to work to exhaust the bibliography of the episode lying at the basis of the action as thoroughly as though they intended to write a history.

…

I said that spectacular works (“scene-painter’s and property-master’s pieces”) called for a far greater quantity of material features than “Tristan and Isolde.” It can be stated of Wagner’s works in general that the properties required for their production are less numerous and that as a rule the scenery is less gorgeous than that required for spectacular opera. Yet it is more difficult to mount a Wagner opera or music-drama than it is to mount the “Queen of Sheba,” “Merlin,” “Aida,” “L’Africaine,” or “Ferdinand Cortez.” The reason is that Wagner’s works call for quality instead of quantity… [The property-master] is confronted with problems of great intricacy, the solution of which requires mechanical genius as distinguished from the mere manual dexterity called for in the manufacture of swords, shields, and numerous other properties. Indeed, the mechanical properties used in Wagner’s works are constant objects of study, attempts to improve them by simplifying the apparatus for working them being made from time to time.

First printed in “Behind the Scenes of an Opera-House”, by Gustav Kobbé. Scribner’s Magazine, Vol. IV, No. 4, October 1888.