The following is the second part of a 1920 article on David Belasco’s property collection. The first part was posted a few weeks ago:

The Array of Relics

by Frank Vreeland

The cabinets which line the walls and occupy the middle of the room have their contents classified and arranged in order. One contains scores of French clocks which have long since ceased to keep tabs on eternity, another has dozens of colonial candlesticks and mediæval lanterns, and a third holds yards of cut glassware of all periods that would cause a high priced smash if any spook started skylarking among them. On wires near the ceiling are strung expensive violins in cases, ancient Indian wicker work which was used in “The Heart of Wetona,” and Crusaders’ helmets with chain mail netting to ward off stings more vicious than the best Jersey mosquitoes could give.

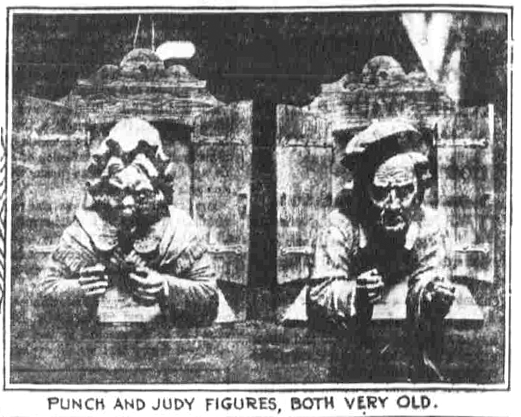

Altogether it is the oddest jumble of the modern and the antique, the civilized and the savage, that could be huddled together by anything outside of an earthquake. An old French mirror, used in “Du Barry,” with its gilt still bright, is hung near an effigy from a venerable Punch and Judy set said to be 150 years old and looking every minute of it. A large painted fan with a mother of pearl handle, reputed to have been the property of Sarah Siddons, is framed just above pictures of Lincoln, Grant, Lee and Stonewall Jackson, while near by are medicine sticks over which Indians made a fuss whenever they had the stomach ache.

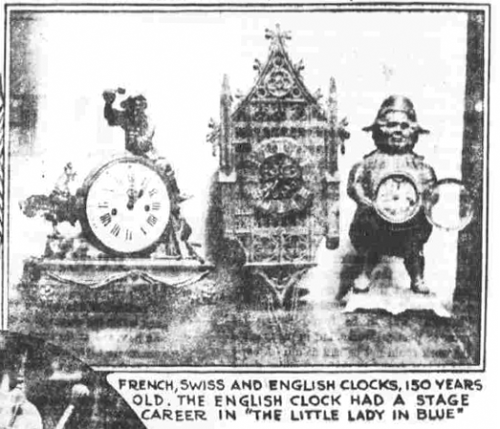

On top of the cabinets roosts an ornate painted handbox of 1820 containing women’s hats of that era that were worn by Frances Starr in “The Little Lady in Blue,” while right beside it stands a large grocer’s tin of graham crackers. In another cabinet is a modern English policeman’s dark lantern, while beside it are two archaic flintlock pistols of Turkish make, a blunderbuss a couple of centuries old, and an old English wine basket—a wooden shovel in which the bottle lay on its side for ease in pouring—which to a modern American would possess a highly antiquarian value.

From the top of a French cabinet—a real antique used in “Du Barry”—a bust of Napoleon frowns down on some papier mache bacon used in “Dark Rosaleen”—and frowns quite properly, when one reflects how the Little Corporal was troubled with indigestion. A bristling French private’s car of the time of the Empire stands near a quiet grandfather’s clock which appeared in that decidedly peaceful play “The Return of Peter Grimm.”

A huge automobile horn that would shake the innards out of a flivver is suspended above a stand in which modern walking sticks jostle gnarled and curly-cued canes of 1810 and 1850, and dainty modern parasols are lined up against a huge umbrella of the earliest type, with whalebone ribs and a spread of over six feet that shows the whole family was meant to be sheltered by it—and that shows the size of the family in those days. A guaranteed Roman breastplate used in “Adrea,” Mrs. Leslie Carter’s vehicle, is placed alongside an innocuous carved Swiss clock, while underneath a great iron bound chest of the Captain Kidd variety, which was part of the setting for “Sweet Kitty Bellairs,” reposes as solidly as though weighted with buried treasure, instead of being stuffed with sofa cushions.

Original Publication: Vreeland, Frank. “Belasco’s Property Room Houses Antique Gems.†The Sun and New York Herald 1 Feb. 1920, Sunday Magazine Section sec.: 7. Print.