Richard Brome was an English playwright of the Caroline Era, coming just on the heels of Shakespeare. In his 1640 play The Antipodes, he describes the inventory of properties and costumes of a typical company at the time. In the scene, a character named By-Play is describing how another character named Peregrine entered the company’s prop room and, thinking everything was real, set forth on “conquering” all the props.

“He has got into our tiring house[ref]The tiring house was a backstage area for actors to change costumes and grab props before going back onto stage (http://www.bardstage.org/globe-theatre-tiring-house.htm)[/ref] amongst us,

And ta’en a strict survey of all our properties,

Our statues, and our images of gods,

Our planets, and our constellations,

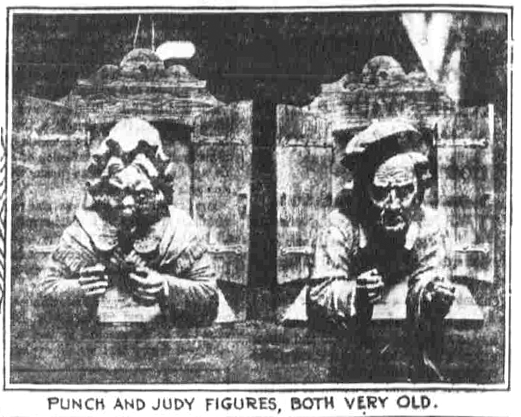

Our giants, monsters, furies, beasts, and bug-bears,

Our helmets, shields, and visors, hair, and beards,

Our paste-board march-panes, and our wooden pies.

Whether he thought ‘t was some enchanted castle,

Or temple, hung and piled with monuments

Of uncouth and various aspects,

I dive not to his thoughts. Wonder he did

Awhile, it seemed, but yet undaunted stood;

When, on a sudden, with thrice knightly force,

And thrice puissant arm, he snatcheth down

The sword and shield that I played Bevis with,

Rushed among the ‘foresaid properties,

Killed monster after monster, takes the puppets

Prisoners, knocks down the Cyclops, tumbles all

Our Jigamogs and trinkets to the wall.

Spying at last the crown and royal robes

I’ the upper-wardrobe, next to which, by chance,

The devil’s visor hung, and their flame-painted

Skin-coats, these he removed with greater fury;

And (having cut the infernal ugly faces

All into mammocks,) with a reverend hand

He takes the imperial diadem, and crowns

Himself ‘King of the Antipodes,’ and believes

He has justly gained the kingdom by his conquest.”[ref]Wall, James W. Rise and progress of the modern drama. Knickerbocker, v.44, July, 1854, p.70. Google Books. Web. 27 June 2016. <https://books.google.com/books?id=zJtdXXOxOK0C&pg=PA70#v=onepage&q&f=false>.[/ref]