A few years ago, a press release came out declaring the history of that most useful of tools, the jig saw. It read:

“The jigsaw is celebrating its 60th birthday. About 60 years ago, Albert Kaufmann, who worked for the Swiss company Scintilla AG, invented the principle of the electric jigsaw. The inspiration for this came from his wife’s sewing machine: the very fast up and down action of the needle. By clamping a saw blade in this sewing machine, the inventor was able to produce extremely attractive curved cuts in wood. This represented the birth of a completely new tool. In 1947, Scintilla began series production of what was called the “Lesto jigsaw”, the first electric handheld jigsaw in the world.” [ref]A Youthful Sixty-year-old: The Jigsaw Celebrates Its 60th Birthday. Bosch Media Service, 4 June 2007. Web. 23 Apr. 2012.[/ref]

With the absence of any evidence to the contrary, this information has spread throughout the Internet, including to Wikipedia. For anyone researching the history of the jig saw, they will most likely find some quoting or paraphrasing of this press release; the fact that it is parroted on so many other web pages may make it appear that it is universally accepted as the truth.

While companies typically use press releases to extol the virtues of their own products and exclude all others, it is lazy for others to use such a press release as the sole citation in a history of the jig saw. The account given is an extremely simplified and unverifiable account of the history of such tools. We can see that better by examining the individual claims in the statement: that it is “the birth of a completely new tool”, that Kaufmann “invented the principle of the electric jigsaw”, and that the Lesto jigsaw was “the first electric handheld jigsaw in the world”. Along the way, we will get a much richer understanding of how many of the tools we use have evolved over time.

“The birth of a completely new tool.”

First, just what is a jig saw? The Oxford English dictionary defines it as “a vertically reciprocating saw driven by a crank, mounted in various different ways.” The term can be better understood by looking at the definition for jig: “To move up and down or to and fro with a rapid jerky motion”.  [ref]Murray, James A. H., ed. A New Dictionary on Historical Principles. Vol. 5, Part 2. Oxford: Clarenden, 1901.[/ref]

A reciprocating saw itself is nothing new; the Hierapolis sawmill from the second half of the 3rd century BCE used a reciprocating saw powered by a water wheel. [ref]Bachmann, Martin. Bautechnik Im Antiken Und Vorantiken Kleinasien: Internationale Konferenz 13.-16. Juni 2007 in Istanbul. Istanbul: Ege Yayinlari, 2009.[/ref]

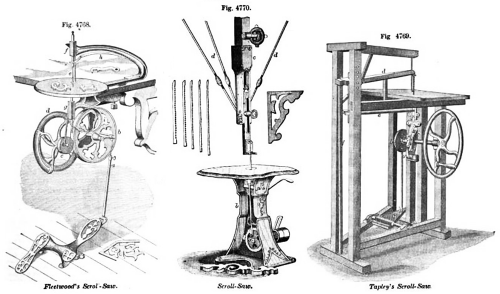

A jig saw is used to cut curves, though. A 1916 book put out by famed saw makers H. Disston & Sons, Inc. explains the provenance of saws for cutting curves:

“As a matter of fact, Fret, Scroll and Jig saws are very similar, and are used for practically the same purpose… The Fret Saw is used almost always by hand… The Scroll Saw, the blades of which are somewhat wider, is used on heavier work, and although frequently worked by hand is also used in a machine run by foot or other power. The Jig Saw, though often confused with the Fret and Scroll Saws, is distinctly a machine saw, and is used on all heavy work…

The Jig Saw resembles Fret and Scroll Saws mainly in the purposes for which it is used. It is a sawing machine with a narrow, vertical, reciprocating saw blade, on which curved and irregular lines and patterns in open work are cut…

A species of Fret Saw is the Buhl Saw. The name of this saw is derived from André Buhl, an Italian. He was celebrated throughout France, in the reign of Louis XIV, for inlaid work in wood.” [ref]The Saw in History. Philadelphia: H. Disston & Sons, 1916, pg 27.[/ref]

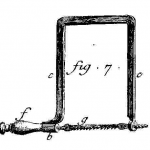

The Buhl saw, characterized by its long, thin blade held on either end in tension, is the ancestor of the fret saw. The earliest illustration of one is in Diderot’s famed encyclopedia, first published in 1751. There, in Volume 2, on page 96, in the second plate for Boissellier (carver), is a small drawing. [ref]Diderot, Denis, and Pierre Mouchon. Encyclopédie; Ou Dictionnaire Raisonné Des Sciences, Des Arts Et Des Métiers, Vol. 2. Paris: Briasson etc., 1751.[/ref]

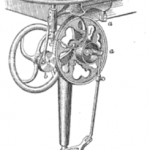

Knight’s American Mechanical Dictionary provides some of the earliest descriptions and illustrations of jig and scroll saws. A jig-saw is “a vertically reciprocating saw, moved by vibrating lever or crank rod… Fig. 2723 is a form of portable jig-saw, which is readily attached to a carpenter’s bench or an ordinary table by means of a screw-clamp.”[ref]Knight, Edward Henry. Knight’s American Mechanical Dictionary. A Description of Tools, Instruments, Machines, Processes, and Engineering; History of Inventions; General Technological Vocabulary; and Digest of Mechanical Appliances in Science and the Arts. Vol. 2. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and, 1884, pg 1215.[/ref] We can see figure 2723, the portable jig-saw, below:

The same book also has a definition for a tool known as a “gig-saw”. This machine is “a thin saw to which a rapid vertical reciprocation is imparted, and which is adapted for sawing scrolls, frets, etc.” [ref]Ibid. pg 965[/ref]

Lastly, the book defines a scroll saw: “A relatively thin and narrow-bladed reciprocating-saw, which passes through a hole in the work-table and saws a kerf in the work, which is moved about in any required direction on the table. The saw follows a scroll or other ornament, according to a pattern or traced figure upon the work.” [ref]Knight, Edward Henry. Knight’s American Mechanical Dictionary. A Description of Tools, Instruments, Machines, Processes, and Engineering; History of Inventions; General Technological Vocabulary; and Digest of Mechanical Appliances in Science and the Arts. Vol. 3. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and, 1884, pg 2077.[/ref]

Interestingly, the dictionary also states, “the band-saw is a scroll-saw and operates continuously.” Indeed, under the definition for gig-saw, Knight writes, “Scroll-saws are usually gig-saws or band-saws.”

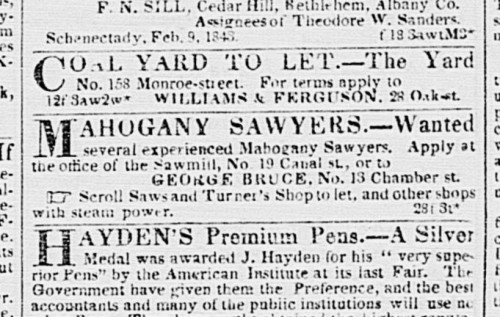

The earliest use of “jig saw” I’ve found is in an 1857 patent, which describes a reciprocating saw method that can be used “for small scroll or jig saws”. [ref]Whipple, Carlyle. Method of Hanging and operating Reciprocating Saws. Patent 16416. 13 January 1857.[/ref] The first occurrence of the term “scroll saw” I could find was in an advertisement in the March 1, 1843, issue of the New York Daily Tribune on the front page.

“Invented the principle of the electric jigsaw”

So it seems strange to claim that Kaufmann’s discovery represented “the birth of a completely new tool,” since the jig saw predates the supposed 1947 discovery by nearly a century, and automatically reciprocating saws in general date back to around 250 BCE. But Kaufmann made his electric, right? That’s the real discovery, isn’t it?

Too bad we have this little nugget from 1933:

“The simplest sort of hand scroll-saws can be purchased for as little as fifty cents. Those of better quality cost a dollar or two. Old-style jig-saws, that are run by foot-power as the older sewing-machines are, can be had at varying prices, but average around twelve or fifteen dollars. You find fewer and fewer of these, however, as the modern jig-saws are nearly all electric.” [ref]Wendt, Carl E. “These Jig-Saw Puzzles.” Boys’ Life Mar. 1933: 16.[/ref]

Not only does this article state that by 1933, electric jig-saws have become far more common than non-electric ones, but it also makes the interesting comparison between jig-saws and sewing machines, which is supposedly the flash of inspiration Albert Kaufmann will have in 14 years.

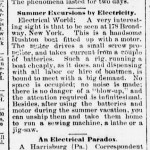

There were, in fact, a number of patents filed in the late 1920s through the mid 1930s for electrifying both scroll saws and stationary jig saws. Electrifying a jig or scroll saw was attempted as soon as possible at the advent of the Age of Electricity. An article in the 1888 Omaha Daily Bee states, “Besides, after using the batteries and motor during the summer vacation, you can unship them and take them home to run a sewing machine, a lathe or a jig-saw.” [ref]”Summer Excursions by Electricity.” The Omaha Daily Bee (Omaha, NE) 9 Jan. 1888: 7. Library of Congress. Chronicling America: Historic Newspapers. Web. 3 May 2012.[/ref]

Seven years before that, an article titled “Electricity as a Hobby” described a shop run in Brooklyn by Dr. St. Clair, a classmate of Thomas Edison. While listing the various novelties which have been electrified in his shop, it states, “The turn of a switch starts a self-feeding scroll saw by electricity.” [ref]”Electricity as a Hobby.” The Sun (New York City) 20 Mar. 1881: 5. Library of Congress. Chronicling America: Historic Newspapers. Web. 3 May 2012.[/ref]

So it would appear the “principle of the electric jigsaw”, claimed as an invention of Kaufmann, actually dates sixty years prior to the date claimed in the Bosch press release.

“The first electric handheld jigsaw in the world.”

But what about their biggest claim, that the 1947 production of the Lesto jig saw was the first electric handheld jigsaw in the world?

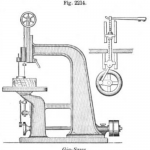

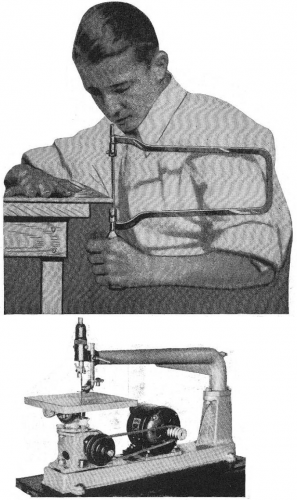

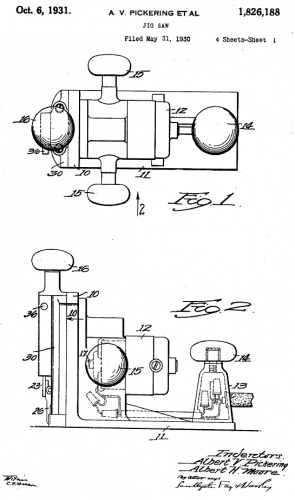

I found a patent issued in 1931 for “a motor-operated jig saw, adapted to cut wood, fiber, metal and other materials, with a simple and convenient operating means; to provide convenient means for manipulating the saw.” This jig saw features “a base having a flat supporting surface so that it can be moved at will over a flat surface.” [ref]Pickering, Albert V. and Moore, Albert H. For a motor-operated jig-saw. Patent 1826188. 6 Oct 1931.[/ref] The drawing below certainly resembles an electric handheld jig saw.

Another patent, this one from 1941, describes providing “the benefits of jigsaw cutting, for example, to a portable tool.” [ref]Briggs, Martin. Power tool. Patent 2240755. 6 May 1941.[/ref]

Of course, patents do not necessarily mean that a working prototype was ever built. Even working inventions do not mean a commercial product was ever brought to market. Indeed, none of the above-mentioned tools seems to have been available for purchase. So while claims of being the “first” electric handheld jig saw in the world are debatable, the fact that the Lesto was the earliest model you can actually buy seems likely.

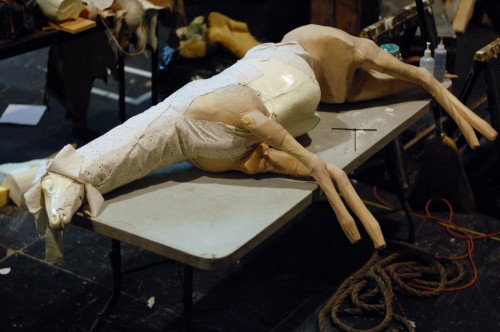

One of the earliest written histories of the electric handheld jig saw comes in 1958. The authors refer to the tools as “electric handsaws”:

“[Forsberg’s] Whiz-Saws were the first American-made electric handsaws. They appeared soon after the Swiss-made Scinta (now Lesto) was introduced into the U.S. in 1945… The electric handsaw has been around ever since the first Scinta saw (now called Lesto) was brought over in 1945 from the world-famous Scintilla Company in Switzerland. Scintilla had been attempting to develop a “portable jigsaw,” little dreaming it would become the husky, all-around workhorse it is today… Scintilla soon had a competitor. Forsberg, working in this country, brought out its now-famous Whiz-Saw, using a similar version of the still-expensive planetary-gear drive… Early sales went to a small and strangely assorted group of professional users, among them stagehands, builders, heating, plumbing and electrical installers.” [ref]Gallager, Sheldon M., and Ralph Treves. “Electric Handsaw: Year’s Most Exciting Power Tool.” Popular Science Mar. 1958: 168-73. Print.[/ref]

An advertisement from eight years prior claims, “The electric Lesto Portable Hand Saw Designed, Manufactured and Patented by Scintilla, Ltd., Switzerland, since 1944.” [ref]The Electric Lesto Portable Hand Saw. Advertisement. The Wood-Worker Aug. 1950: 65.[/ref]

So by 1950, it would appear the story is that Scintilla has been making the Lesto (previously called the Scinta) jig saw since 1944 and has been selling it in the US since 1945. This is pretty good proof that the Lesto was indeed the first electric handheld jig saw you could buy, though I am unsure why the 2007 Bosch press release claims the Lesto was first produced in 1947 rather than 1944.

So in conclusion, the history of the jig saw is a fascinating and complex history and is part of the general evolution of tools over the centuries. I do not mean to knock Bosch (I believe they still make some of the best jig saws in the world; it’s the brand I own), but for all the other websites presenting the “history” of the jig saw, I wish their research would delve deeper than a 97 word press release.