This past weekend I made a trip up to Cornwall, NY, to visit Costume Armour. Brian Wolfe, the general manager, happily showed me around the shop, storage areas and all the pieces they have on display. Costume Armour was founded over 50 years ago by Peter and Katherine Feller, and later purchased by theatrical sculptor Nino Novellino in 1976, and has produced pieces for nearly every Broadway show since then.

The piece that kind of began Costume Armour is the armor from the original Broadway production of The Man of La Mancha. Before then, armor was either leather, felt or heavy metal. They solved many problems by vacuum forming a suit of armor from newly sculpted molds based off of historical research. Though the suit itself predates the company, Novellino made it while working with Peter Feller on the vacuum forming machines built by Feller to construct the Vatican pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair. Costume Armour still has those machines, and they are part of what makes their company extraordinary. The vacuum tank is over 1000 gallons, and they can produce pieces from sheets of plastic as large as 52″ by 12′-0″.

The shop was in the midst of a big order for the Disney Jedi Training Academy, Star Wars Weekends and Celebration, which they have been doing since 2004.

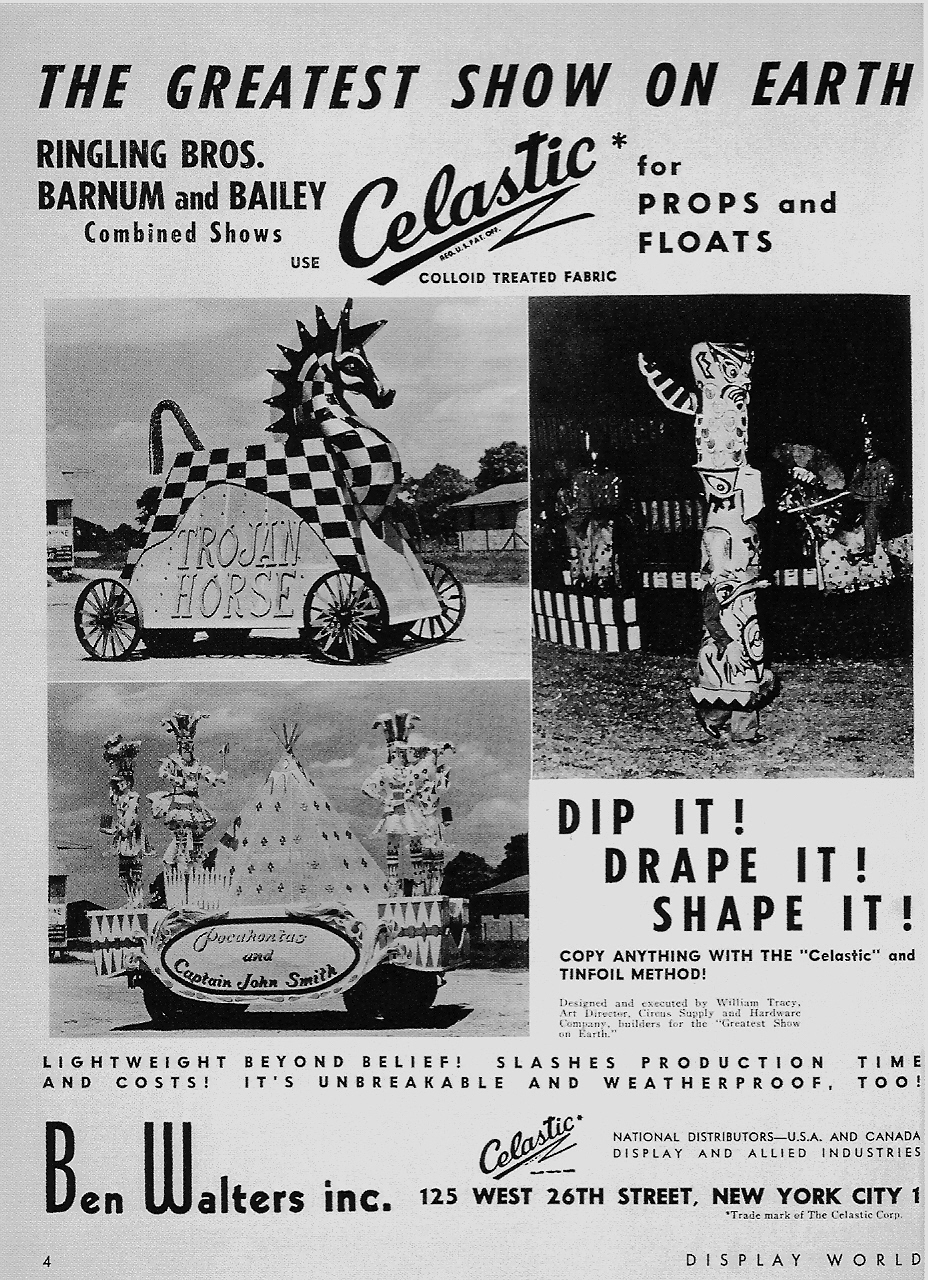

I was interested to learn that the shop still uses Celastic quite a bit for many of their sculptures. The original brand-named Celastic has long ceased being manufactured, though they did have a few rolls stock-piled for those extra-special projects (pictured above). The modern equivalents are a bit thicker, but act the same; the cloth is saturated with acetone, than draped or molded over a form or sculpture, and when the acetone evaporates, you are left with a rigid and rock hard surface. Brian explained that it is unrivaled for making realistically-sculpted drapes and clothes on statues.

So I stand corrected on my earlier article on Celastic, in which I claimed that it is rarely used and that there are less toxic alternatives that can do the same thing. Of course, using it requires the proper safeguards for dealing with large buckets of acetone, but working with most materials in the props shop requires understanding and protecting yourself against any potential hazards and toxins.

While I saw something cool around every corner, I thought I would point out the above picture. They cast a head based off of a scan and model of the Shroud of Turin, so what you have here is what many believe to be the real head of Jesus. He is, of course, on a shelf next to a C-3PO mask.

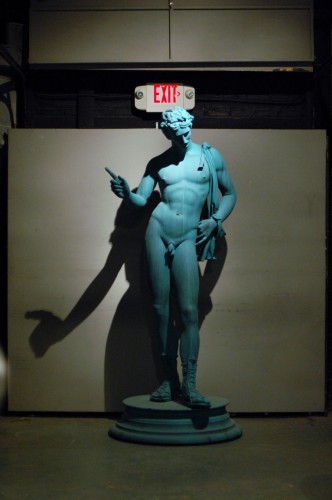

The statue pictured above was produced was was sculpted in foam, molded in silicone and cast in fiberglass . Though larger than me, I could easily pick it up off the ground; most of the weight, in fact, came from the plywood base, and not the statue itself.

Novellino was featured in the American Theatre Wing’s In the Wings series; watch the video to learn more about the company and to see the vacuum forming machines in action.