A design concept which pops up here and there is the “timeless” time period. Especially popular with Shakespeare and Greek classics, the designer and director wish to stage the play so that the scenery, costumes and props do not convey any specific time period. The goal is usually to allow the production to focus on the language, rather than worrying about all the historical minutia which comes from picking a specific time period and the inevitable anachronisms which will be introduced.

The problem which tends to creep up is that while “timeless” means everything comes from a vague time period, the props one uses have to be specific. All objects used by humans are inevitably colored by history and geography. While a designer may have an ever-morphing Platonic ideal of a piece of furniture swimming around in her or his head, the prop master must ultimately choose this furniture from a finite number of pieces.

My boss, Jay Duckworth, and I were talking about the questions which arise between a prop master and a set designer when such a situation occurs. Presented below is an imaginary conversation to further illustrate what might happen:

Prop Master: So I want to pick out some chairs. What period is this show set in?

Set Designer: It’s timeless. It is unrecognizable as any specific time period.

Prop Master: Great. But what period should the chairs be from?

Set Designer: They should not convey any period. They should be timeless.

PM: Okay. Wood timeless, or metal timeless?

SD: What?

PM: Should they be made out of wood or metal? Which is more “timeless”?

SD: Show me some options.

PM: Are they upholstered? Do they have arms?

SD: Whatever looks the least like any specific time period. They should be completely generic.

PM: Like, curvy generic? Or straight generic?

SD: No, they should look like the most representative example of a generic chair you can think of.

PM: So you want a contemporary chair.

SD: No, a timeless one.

PM: Great, we’ll come back to this. Now, there are soldiers in this play. Which country are they from, and which war did they fight in?

SD: They should not look like they come from any specific place or time. They are archetypes of a soldier throughout history.

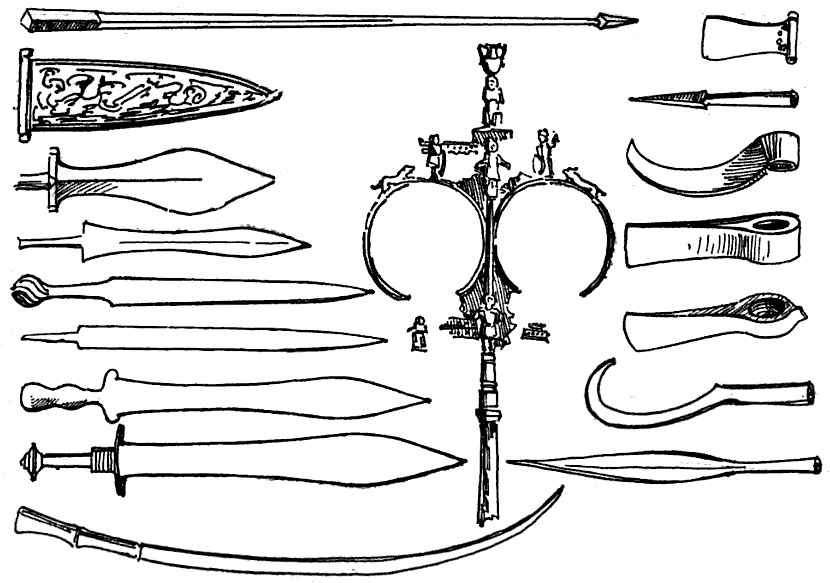

PM: That’s cool. So… should they be carrying guns or swords? Are they from gun times? Or sword times?

SD: Whatever looks the most archetypal.

PM: It’s a pretty big investment to outfit fourteen soldiers with swords, sheaths, and sword belts only to decide later you want to switch to guns. Maybe they could have clubs?

SD: I want something that could kind of be “all weapons”. Something the audience might think is a sword at one point, but makes them think of a gun at another point. Nothing specific.

PM: Clubs it is. Now onto this letter. I just wanted your thoughts because it features so heavily in the action. Do you have any feelings about what the letter should look like?

SD: Like everything else. It should be timeless. An archetype of a letter.

PM: A paper archetype or a parchment archetype?