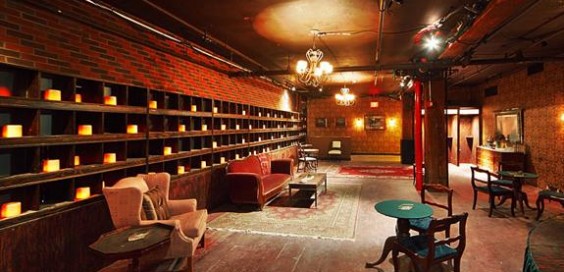

In his book, Thirty Years Ago: Or, The Memoirs of a Water Drinker, William Dunlap describes what may very well be one of America’s first prop masters (or property-men, as they were called then). Written in 1836, it is an intimate look at the earliest theatres in New York City. First, he describes the housing of the backstage workers, which stood behind the theatre:

Opposite to the back or private entrance to this building, stood a lofty wooden pile, erected for, and occupied by, the painters, machinists, and carpenters of the establishment; to the north of which (where now the above-mentioned temperance hotel is planted), were several low, wooden dram-shops, and other receptacles of intemperance and infamy; and to the south, several taller wooden houses, occupied by the poor and industrious; one of which tenements, immediately adjoining the scene-house, was the residence of John Kent, the property-man of the theatre, and his wife. We have seen in the last chapter, that among other properties, he was to furnish a tarrapin-supper for the young manager and his joyous companions. As some of my readers may not be sufficiently initiated in the mysteries of stage-management, I will tell them what a property-man is.

Good to his word, Dunlap describes a property man’s responsibilities circa 1811.

Though, in such matters, I do consider my authority as indifferent good, yet I will first give higher. Peter Quince says, “I will draw a bill of properties, such as our play wants;” and Bottom, who appears to be the manager, gives us a list of beards, as “your straw-coloured beard, your orange-tawny beard, your purple-in-grain beard, or your French crown-coloured beard, your perfect yellow.”

That I may not mislead, let me note, that actors in the year 1811 found their own wigs and beards; but then property beards and wigs were supplied to the supernumeraries, the “reverend, grave and potent seignors” of Venice, the senatorial fathers of Rome, or parliamentary lords of England.

Quince performed the part of the prompter, whose duty it was, to give a bill of properties to the property-man; and these consisted of every imaginable thing. In the Midsummer Night’s Dream, for example, one property is an ass’s head; which, if not belonging to the manager, or one of the company, the property-man must find elsewhere. Arms and ammunition, loaded pistols for sham mischief, and decanters of liquor for real:—(for though the actors could dispense with the bullets, they required the alcohol,)—love letters and challenges—beds, bed-linen, and babies—in short, the property-man was bound to produce whatever was required by the incidents of the play, as set down in the “bill of properties” furnished by the prompter. Such was the office of John Kent, besides furnishing suppers occasionally for the manager, and doing other extra services, for which he was well remunerated, and experienced the favour of his employer.

He then describes the background of the property man, John Kent, and his wife:

Kent and his wife were old. In youth they had been slaves to the same master, under that system established and enforced on her colonies by that nation who at the same time boasted, justly, “that the chains of the slave fell from him on his touching her shores;” that he became a man as soon as he breathed the air of her glorious island; yet, with that inconsistency so often seen in nations as well as individuals, sent her floating dungeons with the heaviest chains, forged for the purpose, to manacle the African, and convey him to a hopeless slavery among her children in America; even refusing those children the privilege of rejecting the unhallowed and poisonous gift. But England has washed this stain from her hands; while the blot remains where she fixed it, and has produced a cancerous sore on the fairest political body that ever before existed.

Mr. and Mrs. Kent were not Africans by birth, but descendants from the people so long the prey of European and American avarice; and by some intermixture of the blood of their ancestors with that of their masters, their colour was that which is known among us as mulatto, or mulatre; still they were classed with what people of African descent (who abhor the word “negro”) call “people of colour.”

A few pages later, Dunlap provides a physical description of Kent himself:

Between the table and the door sat a man of sturdy frame, but time-worn; his age appeared to be sixty. He was darker than the woman, and his features more African. His crisped iron-grey hair thickly covered his head and shaded his temples. His forehead was prominent; with many deep wrinkles crossing it; while farrows as deep marked his cheek. His dress was that of a labourer. It was neat, but here and there patched with cloth that denoted the colour originally belonging to the whole garment. He held his spectacles in his left hand and his snuff box in his right. His eyes, full of respectful attention, were fixed on the figure nearest to the table and lamp; as were also, but with a more earnest gaze, those of the reclining invalid.

Dunlap then reveals how Kent became a property man through a dialogue with Emma Portland, the “heroine” of his memoirs:

“How came you to be brought so intimately in contact with theatres, and theatrical people, Mr. Kent?”

“I’ll tell you, miss. My master wished to give me a trade, and as I always had a notion of drawing, he put me apprentice to a house and sign-painter that lived in John-street, near the play-house: and it was by waiting upon my ‘bos‘ that I got my first knowledge of actors; for as there was no scene-painters then in the country, and he having some little skill, (little enough to be sure,) of that kind of work, he was employed for want of a better; and I ground the paints, and mixed them, as he taught me. So, by and by, as I could draw rather better than bos, I became a favourite with the actors.”

“That drawing over the fire-place, I understand, is one of yours.”

“Yes, miss; but I can’t see the end of a camels-hair pencil now.”

“How long is it since you practised scene-painting?”

“This was in the year seventeen hundred and seventy four, at which time Mr. Hallam went to England. Mr. Henry was the great man of the theatre then, and a fine man he was. When I left New-York, to go to Canada, there were four sisters in the old American Company, the oldest was Mrs. Henry; and when I came back, after the war, the youngest was Mrs. Henry, and the other two had been Mrs. Henrys in the meanwhile, and were still living. This was a long time ago. Things have mended.”

Later in the book, we learn some more of Kent’s early life through another dialogue with Emma:

“I was born, as I have told you, Miss Emmy, in this city, when it was a poor little place compared to what it is now; when the park, now level as a floor, and filled with trees, was called the fields ; no houses, but some mean wooden ones, around it; and neither tree nor green thing to be seen. The people were almost as much Dutch as English. My master took me with him to Canada, when the rebels, as they called them then, were mobbing the tories—for he was an Englishman and a loyalist.”

“He was a good master to you—was he not?”

“Why do you think so, Miss?”

“Because you had a good education for—for—”

“A slave, Miss. You did not like to speak the word. Yes, I was a slave. Yes, Miss, he was a good master; but he was a master.”

“He had you taught a trade, too.”

“That makes the slave a more valuable property. He can earn more wages for his master. Having a trade, he will bring a higher price if set up at auction, to be knocked down to the highest bidder, like a horse or a dog.”

It seems strange that a “memoir” would feature an omniscient narrator and a heroine; perhaps this tale is fictionalized to some extent. Still, the details of the theatre and the lives of its workers would have been based on the realities of the day. Whether John Kent was a real historical figure or not, the first prop masters of America would have had similar lives.